War Stories - How I matured a chaotic startup into a professional development team

A story of a dev-ops adoption and an organization’s transformation from waterfall to agile to lean.

The Beginning of the End?

Engineers were leaving by the droves. We lost seven engineers in months due to a single project. Our turnover had hit a high of a 38%.

It was the beginning of an exodus and an organizational collapse was on the horizon.

What was going on?

We were supposed to be on a solid path. Product ran two-week sprints and performed all of the scrum ceremonies to the T. We had 1:1s with all of the engineers. By any organizational standard, we should have been doing well.

Our problem was that, while on paper we were agile, in spirit we were far from it. We had highly centralized, top-down command-and-control, driven by product management that told the developers exactly what to do and when to do it.

Product’s initiatives weren’t at all aligned with the business. The developers ended up creating feature after feature that the business never used or even asked for.

The project that broke the camel’s back was a multi-month waterfall technology project that provided zero value, was started with little to no planning, and touched every core part of our software systems and business processes. Despite multiple warnings raised by engineers, they were overruled and the project proceeded.

It was an intense and focused effort by the organization to get it done, with the promise from Product that it would solve all of the business’ problems by the end. It was an empty promise but we labored on.

On the one hand, it was great to see that level of organizational alignment. On the other, developers hate death marches. Sure, we ran it in two-week sprints, but a two-week waterfall is still a waterfall. By the end of it, the developers were burnt out.

Enough was enough. The rate of departure was unsustainable and not yet over. As an engineering manager close to team, I knew that more than a few developers were actively looking for other jobs.

We had to make a change.

Who Are We? Product or Engineering?

The organizational structure at the company hadn’t changed much from its startup roots. While the company had scaled by nearly 600%, its processes and structures hadn’t grown to match. The structure was very much the same as its startup roots.

There was no “Engineering” department. It was simply “Product,” which included all of the product managers, designers, and engineers under a single organizational entity. Engineering didn’t have a separate budget, OKRs, KPIs, or even roadmap.

As a result, Product was the sole authority on everything.

This led to a few challenges

It was difficult to prioritize or advocate for Engineering requirements. Things like addressing technical debt would always lose against “the next big product idea” that would (in an ideal world) generate millions of more dollars in revenue.

As a result, the system accrued a significant amount of technical debt over the years, making the development of even basic things like changing the color of a button across all of the pages a monumental effort. We had a joke for it — we called it “load-bearing CSS” because we knew somehow, somewhere, there was critical business logic depending on the color of that button.

It made resourcing and planning difficult. We shared a fungible budget with Product, which meant when an engineer left, that allocation often disappeared, going to either Design or Product, or disappearing outright.

It made it hard to give people raises. Our developers had significant pay disparities as a result of ineffective hiring practices during the company’s hyper-growth phase. Many were nearly 30–50% under market, some were 50% above market. In some cases, people who shared the same level had as much as a 60% salary difference!

Finally, it made engineering difficult. We were subservient to the Product organization, which meant we always had to do what the product manager said, without exceptions. We ended up with a team of ticket takers building tiny things the product manager specified, instead of leveraging our collective problem-solving skills to find a great solution to a problem.

Lacking voice

As far as the rest of the company was concerned, Product was the technology team and, as a result, the product managers were the voice of the technology, design, and engineering.

Unfortunately, the product managers simply didn’t know the technology as well as they thought they did. They had a lot of assumptions about how it was built and how it functioned — these assumptions were incorrect.

Part of the issue was their skill level. Novice product managers ended up drip-feeding information or projects to engineers with no cohesive end vision. As a result, things were built as separate items or as minor add-ons to existing systems. When it was time to make the pièce de résistance, tying them together into a synergistic whole, it was impossible because they weren’t built to be integrated or separated from other parts of the system.

Part of the challenge was the team structure. We had teams that operated at the layer level — front end, back end, and mobile teams. They weren’t cross-functional and each initiative required significant cross-over and synchronization. The result? Unnecessary hand-offs, gatekeeping, and delays on things that could have been executed rapidly with a single cross-functional team.

This happened repeatedly. When product managers communicated their features to the rest of the company, they were assumed to have wildly different capabilities than what was actually built. However, because product managers were viewed as the voice of the technology, their inaccurate statements were taken as gospel by other parts of the organization, leading to significant confusion.

Engineering needed a distinct voice.

How did we get there?

Like any major organizational transformation, it took a lot of conversations and a few lucky breaks.

The first issue to solve was the layered teams. This was relatively straightforward to fix — have engineers work in full-stack teams. This meant mixing engineers of varying skills into each team, removing the layers.

Once that was proven to work better, it was time to illustrate the need for separate departments. I talked about the confusion and development issues it caused to have them combined. I talked about how it was still possible to maintain collaboration and organizational cohesion even with the departments separated, citing the success of the newly formed full-stack teams as an example.

I emphasized the need for a leadership structure that represented engineering needs and could manage engineering-related personnel and structural issues.

I came prepared. I had everything from desired org charts to career progression ladders to budgets. I talked about team structure, development processes, with anyone and everyone who would listen.

I worked directly with executive stakeholders as well as middle managers and ICs throughout the company to share this message and understand the problems it would cause or solve, and then summarized them the essential details for the executive team.

We eventually got buy-in from executive stakeholders and thus formed the PED team — Product, Engineering, and Design as separate departments working collaboratively. I became the Director of Engineering responsible for the newly formed Engineering department and all of its developers.

This meant we had our voice, our autonomy, and our budget.

First Stop: Fair Compensation

As previously stated, developer compensation was all over the place and completely divorced from actual performance, by as much as 60%.

It’s not a great strategy to have that significant a pay disparity for the same quality of work. Pay disparities demotivate high performers who wonder why they should work harder to earn less and it causes low performers to become complacent. After all, if high performance isn’t necessary to achieve their desired salaries, that’s one less thing motivating them to improve and perform well.

I put a stop to that as soon as I could. One of the first things the separation enabled me to do was level pay bands across the board. Working with our finance team, I brought Engineers who were significantly under market up to market. One of the biggest gripes engineers had was about their compensation and I ensured that hygiene factors were met so we could focus on more important issues.

I provided clarity and reset expectations for the engineers who were significantly over the market level. For some, I made it known that their salary expectations were simply unrealistic given our company and their skill level. For others, it was about focusing them and providing them training and professional development so that they could perform at the level that matched what they were getting paid.

In some cases, the conversations turned into performance improvement plans. Some employees improved and thrived. Others didn’t and parted ways with us. I ensured a portion of departing employee salaries was re-invested back into the current team, enabling me to level up the employees that were performing well or improving.

Names Give Power — With Power Comes Responsibility

Because we were now the engineering department, we had some responsibilities to the rest of the company. They needed visibility of how our organization was performing and whether this change was worth it.

Numbers for everyone

We were in a position where the metrics we were looking at weren’t particularly useful. We had product metrics like velocity for team-level capacity, but not much else. We couldn’t use them to see where we were on our journey of continuous improvement.

We experienced lucky timing. The State of DevOps report had come out, which provided an easy-to-adopt set of metrics we could use as the foundation for our culture of measurement. As an avid fan of the book “Accelerate,” it was a great reminder of the existence of a set of principles for engineering success.

We took the four basic ones:

Cycle time.

Mean-time-to-restore.

Deployment frequency.

Change failure rate.

We hadn’t measured any of these in the past. I looked at some tooling to retrieve these, but they were complex, not quite what we needed, or were pricey. We simply didn’t have the resources to devote to exploring them. Besides, it wasn’t the greatest idea to suddenly increase costs by hundreds or thousands of dollars, right when the engineering department started. We first needed to prove ourselves.

We took the DIY approach. I immediately wrote a bash script that took our Git commit data and calculated the deployment frequency from it. I also wrote a second script that took the same Git data and estimated a change failure rate, looking for words like “hotfix” and comparing it to the deployment frequency.

I also implemented a process to manually document every single incident or outage — including timelines, when it started, when it was detected, when it was resolved, what the root cause was, and what actions were taken subsequently. It was documented in a Github issue, which was fully available to all of the engineers. Through this, we had our mean-time-to-restore — at least manually.

I couldn’t figure out how to get cycle time from what we were already tracking, so I took a proxy measure of lead time. I created a spreadsheet that took our JIRA issues and estimated lead time based on the time an issue was created and when it was resolved. It wasn’t precise or accurate, but it was a good enough ballpark to get a picture of where we were.

The results weren’t pretty

Looking back at the data as a benchmark the result were disappointing, to say the least.

Deployment Frequency was at 0.25 / day. That means we deployed, on average, once every four days. Digging deeper into the numbers, it was often small tweaks and bug fixes — feature deploys were happening a lot more rarely.

Our Change Failure Rate was 25%, which meant one out of every four deploys required a hotfix. Looking into data even earlier, our change failure rate at one point had hit 400%, meaning every deploy led to four hotfixes.

Our mean-time-to-restore was roughly eight hours. This was driven primarily by a database outage that we simply weren’t prepared for.

Our Lead Time was 14 days — coincidentally, the same length as a sprint. I guess that work does always fill the allotted time!

Getting Lean

There’s a lot of overlap with DevOps and Lean principles. Post-agile foundations just don’t change. Reducing batch size, creating and driving feedback loops, iteration — these are all things we could do.

However, the technology didn’t enable it. If I were to tell our team “we should deploy every day,” it would be impossible to do without greatly negatively affecting our output.

Our deployment took nearly half an hour. We didn’t have a staging environment. Our tests failed regularly for random reasons.

It was a chicken and egg problem — how do we improve our process, to improve our technology, to improve our process, to improve our technology…?

Starting With the Principles First — Small Batch Sizes

One of the principle practices of Lean and DevOps is risk reduction via small batch size. By reducing the risk of every deployment, we accelerate our ability to deliver by improving confidence and stability in our delivery process.

Our technology platform was not conducive to delivering anything without a big-bang release. We would have long-lived feature branches where everything would go (via the git-flow approach, which I introduced when I first started). These branches may have had several thousand lines of code be deployed all at once.

It’s because we didn’t have the capability to deliver small parts without impacting users.

The solution? Create the capability.

Feature Flagging to the Rescue

I set out to create a feature flagging infrastructure within the platform to enable us to toggle features off and on in a consistent way. My hope was that this would encourage the deployment of incomplete features but good code, which meant it would reduce batch sizes/deployment sizes.

This wasn’t as easy as it sounded. Over the years, multiple pseudo-flagging techniques were littered throughout the system. Some things were using ENV variables, others were using hard-coded conditional checks, and more. We even had columns that represented feature flags for a given table!

Managing and integrating all these to work consistently was a challenge that took more than a few phases. It was made more difficult by the way our system was designed — we had to approach system-level feature flags and context-level feature flags in separate phases due to legacy code.

We stuck to the basics. We moved all our feature checks behind an interface, built out a service class to encapsulate all of the various different kinds of flag checks we used. Once we transitioned everything to use the new service class, we created a new data model to hold the feature flags and ran both systems in parallel. After the system was proven to work, we sunset the old data model, then finally deprecated the old code. We also performed a developer training to ensure all the developers knew about the new feature flagging system and how to use it.

Once we had the service layer and data model controlling all feature flags in our platform, extending its functionality with even more power was easy. We added A/B testing, flag options, and more!

Because the interface was built in a generic way, we could easily swap it out with a more robust flagging library down the line without a problem.

Deployment != release

Feature flagging led to the separation of a deploy from a release — a terminology difference that people previously didn’t even consider within the realm of possibility. A deploy was a code integration and delivery into a production environment, whereas a release was a feature becoming used by one or more users.

An Unexpected Surprise

Surprisingly, the introduction of feature flags actually improved interactions between Engineering, Product, and Design.

There was always a tension between building things right, building the right thing, and building things right away.

Feature flagging made engineers happy because it helped de-risk large projects by providing a way to integrate and get things out quickly. Engineers started to deploy code earlier in the development process, which prevented code from piling up into massive, risky deployments.

It made product managers happy because they could test the business impact of an idea with less risk but still control when it went out. They could release a feature when they wanted, or test it on smaller audiences to manage risk and get feedback early without drastically impacting the business. If the feature didn’t work as intended or caused issues, they could easily turn it off with the click of a button. Features could be iterated multiple times to get the kinks out before a wider release.

This, in turn, made designers happy because by deploying things, but not releasing widely, they could be iterated on to eventually match design fidelity. It helped us to ensure we didn’t deliver subpar interactions and experiences to customers.

It was an unexpected but welcome effect on team collaboration. I won’t say feature flagging was the silver bullet to our collaboration problems, but it sure helped us realize that we all had the same goal in mind and get over the smaller execution quibbles.

Small Batch Sizes = More Batches = More Overhead

The feature flags helped reduce risk and batch sizes somewhat but we were still deploying releases with nearly a thousand lines of code.

Why?

Our deployments were painful. It took 30 to 45 minutes of a developer’s full attention, merging PRs, writing release notes, and performing smoke tests.

As a result, most developers hated to deploy. A few dedicated engineers did most of the deploys, while the rest cheered them on.

The frequency of deploys was low under this model. It only happened a few times week and each of the deploys was still relatively large and risky.

We needed to reduce the overhead of producing the batch/deploy.

Automation to the rescue

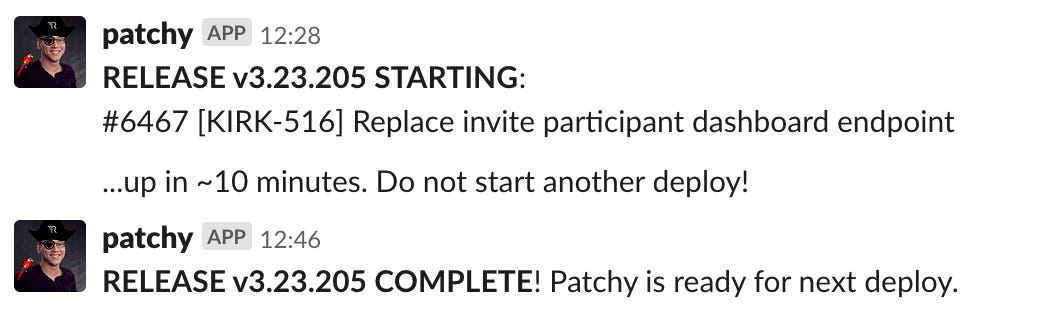

I wrote a tool in bash to automate this tedious process, at least for some of our deployments. The tool, which we called Patchy, allowed any engineer to create a release out of a single PR, and deploy it straight to production with a single command.

Running ./patchy.sh 6486 would deploy PR #6486, for example.

It handled everything related to the deploy that was previously taking up the developer’s attention: release notes, incrementing version numbers, checking the test results, and even notifying people with the notes.

Patchy reduced the time it took a developer to deploy from 30 minutes to just one minute. While the deploy itself took roughly 15 minutes, the developer simply triggered it in a “fire and forget” manner.

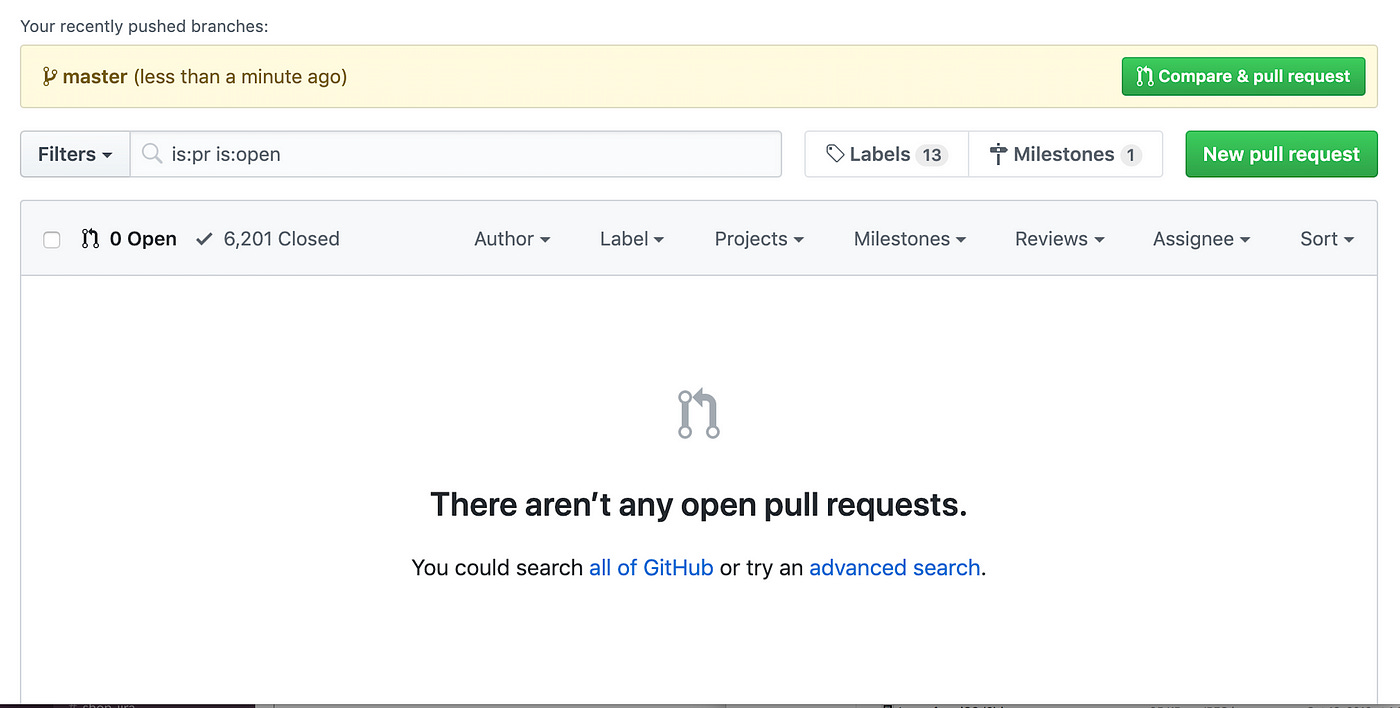

The results were instantaneous. Deployment Frequency went from 0.25/day, to an average of 6.5/day. More developers were involved in the deployment process. Gone were the 15–20 PR queues. We even had some days where we hit zero PRs open without a reduction in our productivity or output.

Increase deployment batch size

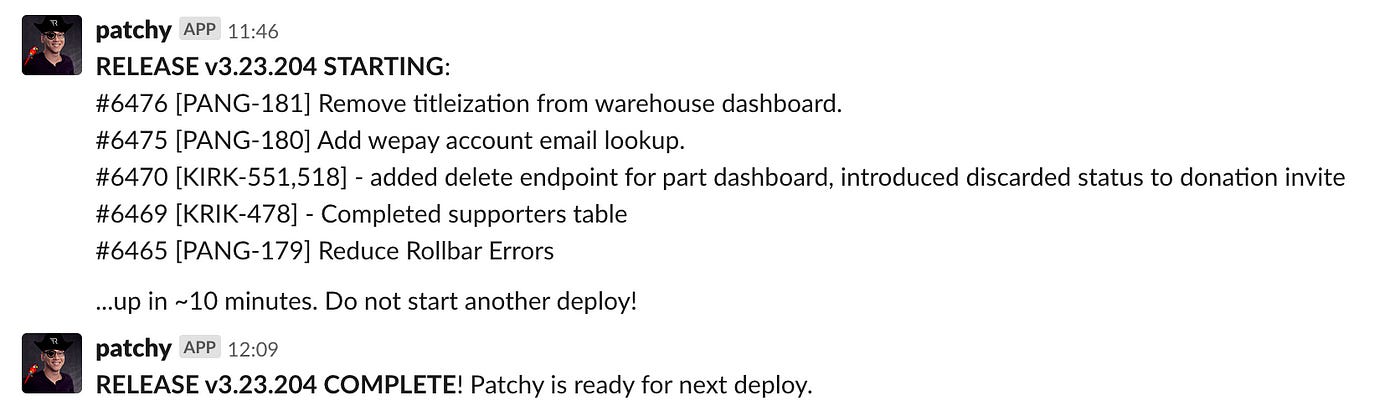

One issue we encountered was that, while our deployment frequency was high, the smaller deployment batch sizes led to an increased overhead when deploying multiple items.

We had “deploy trains” where engineers would take turns “Patchying” their PRs. These deploy trains would sometimes run for hours — an engineer would run Patchy for their PR, sending a deploy automatically, and once it was done, another engineer would run Patchy for their PR, and so on and so forth. This led to a stream of changes that, while good on the surface, were indicative of inefficiency.

I rewrote Patchy into a Ruby script, adding the capability to specify multiple PRs to deploy.

By enabling Patchy to deploy multiple items in an automated way, we were able to reduce the cost of deploying multiple things by slightly increasing the deployment batch size.

The result: a drop in deployment frequency to about 3/day without an accompanying drop in the change volume. The number of items actually being released didn’t go down at all.

I carefully monitored the change failure rate and didn’t see any increase. People were still careful to keep their releases low-risk: Trusting your engineers pays off!

Patchy V2 simply removed the overhead of deploying multiple things.

Iterating on Metrics

Around this time, I was able to update our tracking capabilities. JIRA had released new project types (thank you Atlassian!), which allowed me to automatically set timestamps and other items based on when items moved into certain statuses. This allowed me to automatically calculate cycle time, distinguishing it from lead time.

I also implemented automated uptime monitoring, using a combination of Pingdom and Statuspage. This allowed us to have basic server checks that ran once a minute and sent us an alert if our site returned any issues.

In the interest of transparency, we also shared the status page with the rest of the company, providing operations, sales, and other departments an inside look at our uptime to help hold us accountable.

It’s Not Just About the Technology

A lot of people equate DevOps with technologies. When they hear “DevOps”, they think of Docker, Kubernetes, etc. Some think of practices — containerization, orchestration, etc.

For me, these are just tools or methods to accomplish a cultural shift. DevOps begins in the mind and its primary focus is shifting the mindset and culture.

One of the biggest blockers to shifting towards a DevOps model on our organization was our own mindset towards change, ownership, and responsibility.

It had to change.

Ambiguity and the Unknown

“Ugh, the requirements changed.”

“Change” had become a bad word.

The team was not comfortable with ambiguity, to say the least. Previously, the highly centralized work was expected to be finely planned, intricately detailed, and perfectly accurate before being handed off to engineers. This was a result of a building mistrust between Product and engineers.

Any changes or missing information led to an outcry of “incomplete requirements!!!” and many complaints and grumblings from engineers. Perfect requirements are an impossibility, of course, but that never really occurred to the team.

It was a huge shift to get engineers comfortable with being adaptable.

“Change” had become a bad word. If we wanted to succeed and truly be agile, we had to embrace change. I immediately started a counter-culture that was tolerant and accepting of change, shifting the perspective to a new mindset where change was an opportunity to gain more insights into what reality represented.

Making the problem visible

Sometimes, there’s no better way of showing there’s a problem than to visually show it.

I made the lead time metric visible to everyone by publishing the graph on the shared TV in our office area to force the developers to visually see what the impact of demanding perfect planning and detail was. I shared it in 1:1s and meetings.

It was a drastic metric. Some requests waited over sixty days in planning before they even started getting worked on. From a customer’s perspective, that was nearly two months before anything happened — no wonder people in our organization felt Product was a black hole for requests!

Solving the problem

Now that the problem was visible, I could explicitly address it.

I encouraged limits to the length of time we planned items as a forcing function to force things to not be fully fleshed out. We encountered real analysis paralysis and encouraging short lead times improved the team’s adaptability.

Short lead times, however, led to more ambiguity in the requirements. I did significant 1:1 training with the engineers, leads, and product managers to overcome the reluctance to work with less detail. I taught them the kinds of questions to ask and the problems they should look for, and the solutions they could find on their own.

I gave them strategies and tactics for dealing with ambiguity, such as making the “70% decision,” or “guessing right.” I taught them architecture and patterns to help make their code more flexible and less dependent on policy details that could change at any time.

These foundational techniques helped them to get more comfortable with the loss of explicit detail, and also pushed them to leverage more of their own problem-solving skills.

Sure, some project requirements were rushed in the short-term, but the long-term positive impact on culture was invaluable. It might have been an uncomfortable experience, but it greatly improved the team’s capability to adapt and operate with ambiguous information.

Planning for the Future vs. Planning for the Never

While we had made progress in reducing lead times, Product direction still operated in a long-term manner that wasn’t adaptive to changing business needs. Roadmaps would be planned three months to a year out.

Startups change drastically in short time frames. The company’s focus might be one thing in one month, then completely different in the next. In an environment where change is the only constant, why attempt to create a 12-month roadmap?

Forecasts of the long time horizons would go out of date quickly. Worse, a month into the roadmap and we’d know better about our environment and problem, making our roadmap moot. Why stick with it when we know it won’t last? How do we change that mindset?

In an environment where change is the only constant, why attempt to create a 12-month roadmap?

Failure is an option and a darn good one

All of the changes we made in our culture and technology had a massive benefit — it made it cheap to fail.

Reducing the cost of failure allowed us to pursue opportunities that might have previously been incredibly risky or needed to be highly planned in the past. Getting it wrong doesn’t matter when the failure is easy to reverse, or the scope and impact are limited.

I formed a team with a couple of engineers with the sole intent of focusing on the opportunities the business wanted to pursue — those that had a high likelihood of failure, or that weren’t thought out that well. These were often the interruptive tasks that previously annoyed teams and took their attention away from the roadmapped items.

To execute with this team, we practiced Kanban and adopted lean principles. Other teams were running Scrum with all of its ceremony and pomp, but I felt it wasn’t the right approach for this team.

We wanted to be a quick reaction force — a nimble team capable of adapting to the whims of the business. We couldn’t have a quarterly roadmap and do that at the same time. As a result, I ran the team with no roadmap, keeping a close eye on our queue size and ensuring we never planned more than the next week’s worth of work.

Some of the product managers viewed this approach as chaotic and unaligned with the roadmap. They argued it was taking valuable manpower from the planned work we had.

I disagreed. I viewed it as a supportive effort for the product roadmap. By taking on all of the interruptive projects and demands of the business, it freed up the other teams to focus on the main efforts of their planned roadmaps exclusively.

You know what? It worked. The business threw problem after problem at us and the lean team adapted immediately and executed on it. We were able to protect the rest of the teams from these projects, which if we hadn’t done would’ve had to be done anyways, except on a much tighter schedule. While the other teams churned away on a predefined quarterly roadmap, our team was able to handle the business’s urgent intake requests.

The business was happy. Previously they had no ability to change or influence the direction of the product development once it was set. Now, we had a collaborative relationship that allowed us as an entire product development organization to make progress on roadmapped items while still remaining adaptable to business needs.

Other teams later adopted this lean execution model, although not to the extent of the quick reaction force I set up. By limiting their forecast and roadmapped projects to a month or two, they avoided doing extra work on items that would never get executed. They would also leave their roadmaps open to responding to the feedback they got from customers about their release. This meant we started listening to the customer more, which led to better feedback loops and more iterative execution.

By adhering to lean principles, such as work-in-progress limits and managing queue sizes, teams were able to build a backlog of work that was useful for executing and communicating, but adaptable and still responsive to changes found in feedback and business direction.

Promoting Decentralized Control

We were moving faster and delivering more and more, and the speed was uncomfortable for some. The speed, combined with all of these changes and the increased ambiguity, led some people to try and involve themselves in every decision and meeting in an attempt to keep abreast of all of the things that were happening. This led to slowdowns as their gatekeeping became bottlenecks in execution and delivery.

This wasn’t sustainable or effective and the lead engineers had to change their mindsets.

The question becomes, “how do you encourage lead engineers that were previously very centrally controlled to get out of their comfort zone and start making decisions?” When people have operated for a long time under a central command model, it becomes second nature for them to ask for permission and just do what they’re told.

“Learned helplessness” is contagious. It’s a culture shock to be thrust into a situation where you have full freedom with no warning.

We started small

We started small. We provided decision-making capabilities to people who had proven their competency. We limited the scope enough to ensure we didn’t go astray and that we could easily recover from bad decisions.

I personally coached lead engineers and other promising junior leadership on how to flip the mental model of leading. I talked to them about being tolerant of failure, leading with intent, asking not telling, and other foundational practices intending to build a culture of initiative. I taught them that by letting go of direct control and oversight, they would get teams able to make local decisions in a timely manner.

By providing intense clarity and alignment, you can indirectly promote autonomous decision-making that’s beneficial to the business.

The culture wasn’t for everyone

When you define a culture, some people are going to opt-in, and some people are going to opt-out.

It was a long journey. Unfortunately, not everyone followed us on that journey.

Some people just don’t operate well with ambiguity, or explicitly do not want that kind of working environment. That’s OK.

That’s the downside of defining a culture. When you define a culture, some people are going to opt-in, and some people are going to opt-out. It’s a choice every person makes.

I wish those that opted-out the best of luck!

Was It Worth It?

Did all of these efforts work? Were they useful at all? The answer is a resounding yes!

Organizational culture

The company used a tool called 15Five to do a quick weekly survey of the team, asking how their week went. I added additional questions from the Accelerate Westrum Organizational Culture survey in the 15Five to measure the results on the engineering team.

The idea is straightforward: If the biggest predictor of effective organizations is job satisfaction, how do you measure the factors that lead to increased job satisfaction? Westrum created a model for the factors correlated with an organization’s health. We took those factors and surveyed our team regularly over the year.

As we transitioned through our cultural shift, results went from an average of 3.1 to 4.3. It was a massive leap that signaled that we were on the right track.

Retention

Our retention numbers improved significantly as well. That year, only three developers quit — two for personal reasons and one for performance reasons.

People weren’t leaving because of our company anymore.

Delivery

Our delivery improved significantly in both speed and quality.

We were operating by every metric three to five times better than we ever were before.

Our cycle time had hit a low of three days. Our change failure rate went and stayed below 2%. Our deployment frequency hovered around 3.5 deploys / day after the introduction of batch deployment tooling. We introduced change volume as a counter metric and consistently released roughly 120–180 pull requests a month.

We released a multitude of changes that drove significant increases to retention, acquistion, and revenue. The business was happy — they were seeing tangible progress and results on a consistent basis.

Technology

On the technology front, we greatly improved the stability, performance, scalability, and security of our systems. We developed subsystems that helped us develop even faster — design systems, modular component libraries, isolated subsystems, etc.

The delivery of business value didn’t sacrifice the technical quality and the technical quality didn’t sacrifice the delivery of business value. It worked harmoniously.

Improvements

In just one short year, we had drastically transformed how the development organization operated. The changes we made proved to be effective. We were now releasing multiple times a day and had multiple experiments and tests running at any given time.

What’s more, the way we operate had led to better operations across the entire company. The company collaborated better and was more aligned than we had ever been.