On organizational structures - The Core/Focus model to balance stability and innovation

Invest in the ability to innovate while supporting your core business.

A big challenge I’ve experienced several times as successful startups scaled up was being able to do everything needed to keep the product running while still investing in high-impact, innovative new products.

Small startups often have an “everyone does everything” mentality, from the contributor up to the executive. People were conceptually interchangeable and could wear a lot of hats. Allocation often occurred at the granularity of an individual - specific people were assigned to projects and new areas, responsible for delivering it all.

As the number of focuses grew and the complexity of their interactions increased, it became harder and harder for the people involved to be effective. Breadth and depth far exceeded the original scope of the work, and it became too much for any one person to reasonably be effective.

Resource limitations were often the constraint of being able to both innovate and support, which made every decision a prioritization and allocation battle.

Conflict between Product and Engineering leaders increased, as obsession over time spent on ROI (Return on Investment) and how much to place on BAU (Business as Usual) flared up into full-blown arguments.

Product leaders, desperate for more progress, pulled from efforts that kept the lights on. Engineering leaders, desperate for stability, rejected new innovation projects to err on the side of safety. At its worst, this contentious relationship produced a lot of blaming, finger-pointing, and whiplash back and forth. Sometimes, one of the parties succeeded entirely, resulting in the company becoming unstable and collapsing due to an over-focus on innovation, or stagnating and losing in the market due to an over-focus on stability.

To solve this, leaders often decided on extensive meetings, detailed demands for justification of any spend, and precise explanations they were heavily involved in, resulting in extremely slow prioritization and execution delays that further exasperated the issues.

The pain is felt across the company

As one can imagine, contributors felt this pain acutely. All you had to do was ask any team for feedback, and you’d hear things like:

“We’re doing too much”

“We don’t know what we own”

“There’s a lot of whiplash”

“Leadership doesn’t understand the thousands of tiny things needed”

“We’re wasting too much time on these tiny things”

“My work doesn’t matter”

It’s painful for contributors to work effectively in an environment like this.

The fact is both Product and Engineering are right and wrong. You need a stable product so your users and customers keep using it, and you need new innovations so you can acquire new revenue from customers and users. It’s neither group’s fault.

The root cause of these issues stems from an organizational structure that isn’t aligned with the reality of the work. In situations like this, I’ve found a change to the organization structure that embraces the differences in the structure itself can align expectations with reality and achieve both desired outcomes.

Core/Focus

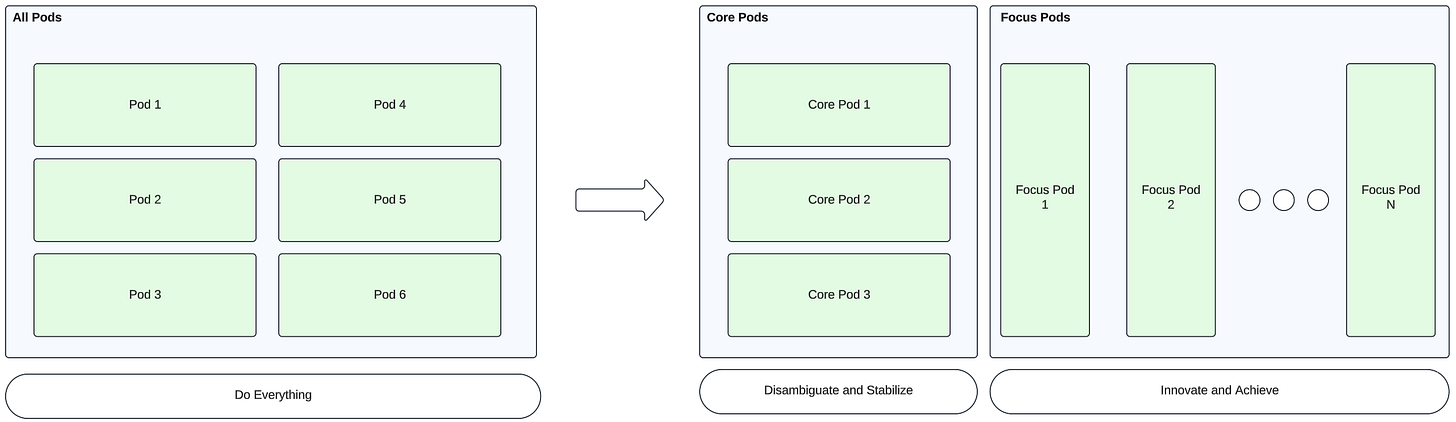

The structure is simple. Instead of expecting that every pod will be involved in doing everything, segment the pods into two types of pods - Core and Focus.

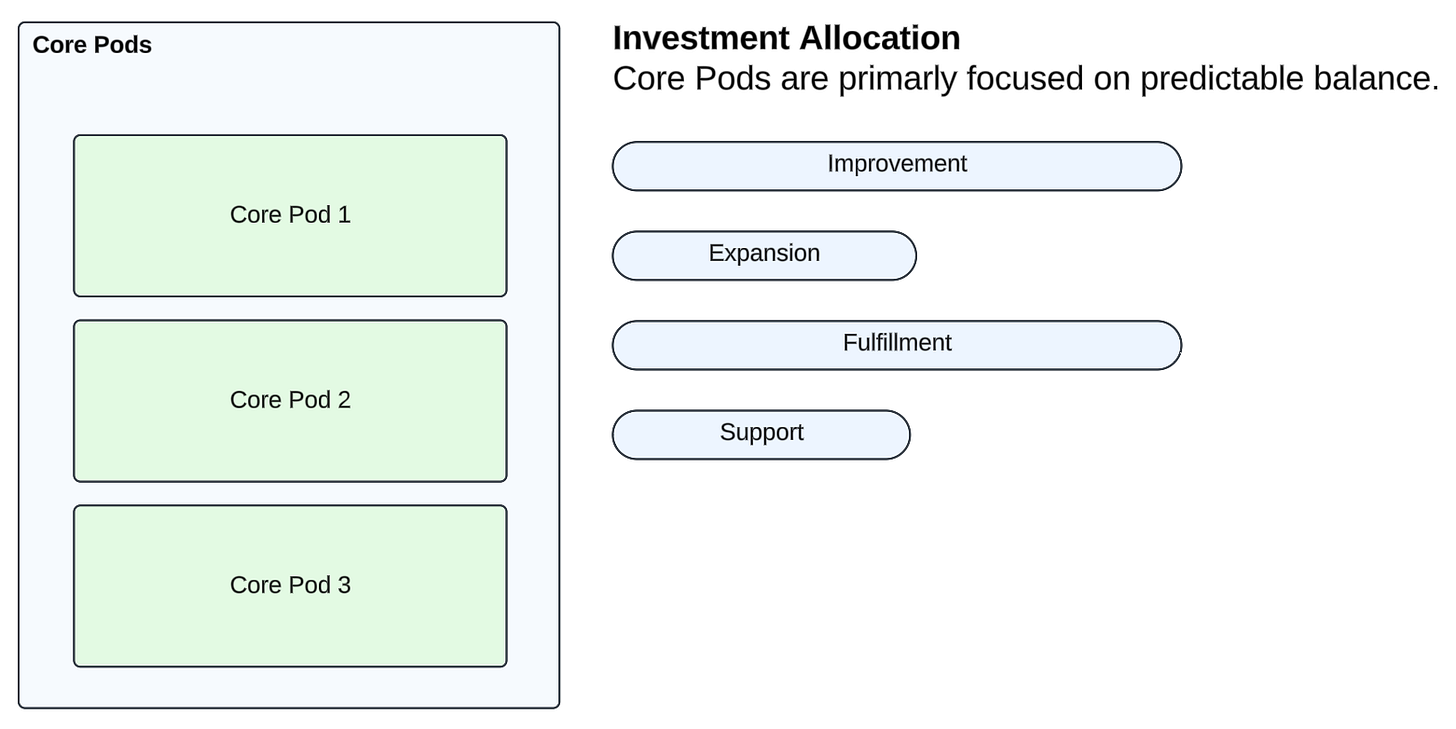

Core

The objective of Core pods are simple: keep the business running with stability.

They should have a predictable roadmap. The Core group should work in a manner where the execution and progress is highly visible - people in the organization should know what is needed, when it will be delivered by, and have solid delivery expectations.

This is the heartbeat by which other parts of the organization match their pace. Marketing can understand a release schedule. Sales can understand their commitments they can make. Support can achieve operational SLAs.

Incremental improvements can be roadmapped, planned, and executed. Known capacity can be used and planned for. Execution is predictable.

To succeed, the Core group needs the ability to say “no” and “when”. Emergencies can occur, but they need to be able to create the predictability necessary to execute well.

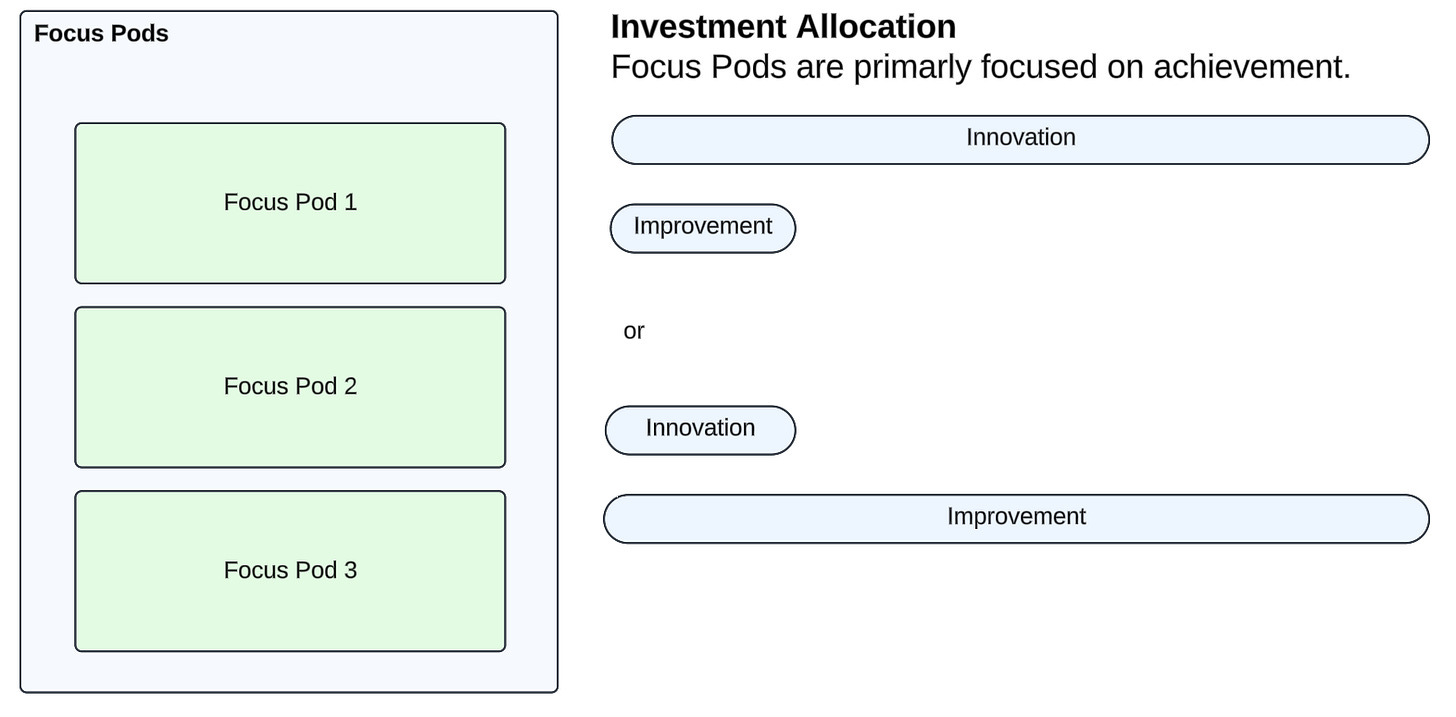

Focus

Focus teams, as the name implies, focus on a particular stream of work. Their job is simple: achieve the outcome they were tasked.

Focus can be on any number of things:

Growth goals, such as to “improve user activation by 15%”

Project goals, such as “unify product listings across our products”

Problem goals, such as “our documentation is terrible - how do we improve it“

Domain goals, such as “own anti-fraud capabilities”

or other properly scoped area.

The important part of the team is that they get to focus on that particular area or outcome for a set period of time - whether that’s 6 weeks or 6 months. At the end of that time period, an evaluation can occur as to whether they achieved their goal, whether it’s worth continuing to invest in, or whether it’s time to move on to something else that’s a higher priority.

Focus teams should have the autonomy to make decisions that lead to the desired outcome, working closely with an appropriate but minimal set of stakeholders.

They shouldn’t have to run decisions by 5 other teams, or have to justify every decision they make to external stakeholders. They may do so internally - that is, evaluate the set of items that might lead to their goal and prioritize it, but they shouldn’t need to do so externally. The investment has already been made, there should be no further justification needed.

Focus teams also need the ability to focus. Yes, that means they should be able to ignore things not within their focus they were given. Whether that’s other urgent/important projects, bug fixes in unrelated parts of the product, or even developer UX. Their primary goal should be their main effort they have been assigned.

What does this enable?

This structure enables aligned expectations from the executive and management team down to the individual contributors. Team members on the focus pods know that they won’t be distracted by 10 other streams of work, and should focus on solving their key problem. Team members of the Core pods know that they won’t be dinged for not finding needle-moving opportunities, and can take satisfaction from a job efficiently completed and a problem avoided.

Organizationally, it also enables the business to execute at scale. Businesses have a clear mechanism for entering a new market or launching a new product or focusing on a new business initiative - spinning up a focus pod.

Why does the structure work?

To first understand why it works, you first need to understand the mental model for how to model the kind of work being done and what’s required for each type of work.

Just remember: all models are wrong, some are useful.

Understanding the different kinds of work

In an organization that develops, operates, and sells a product, you see a variety of different kinds of work as the business operates, comes up with new ideas, and the system evolves.

The kinds of work you might encounter can be bucketed into the following groups:

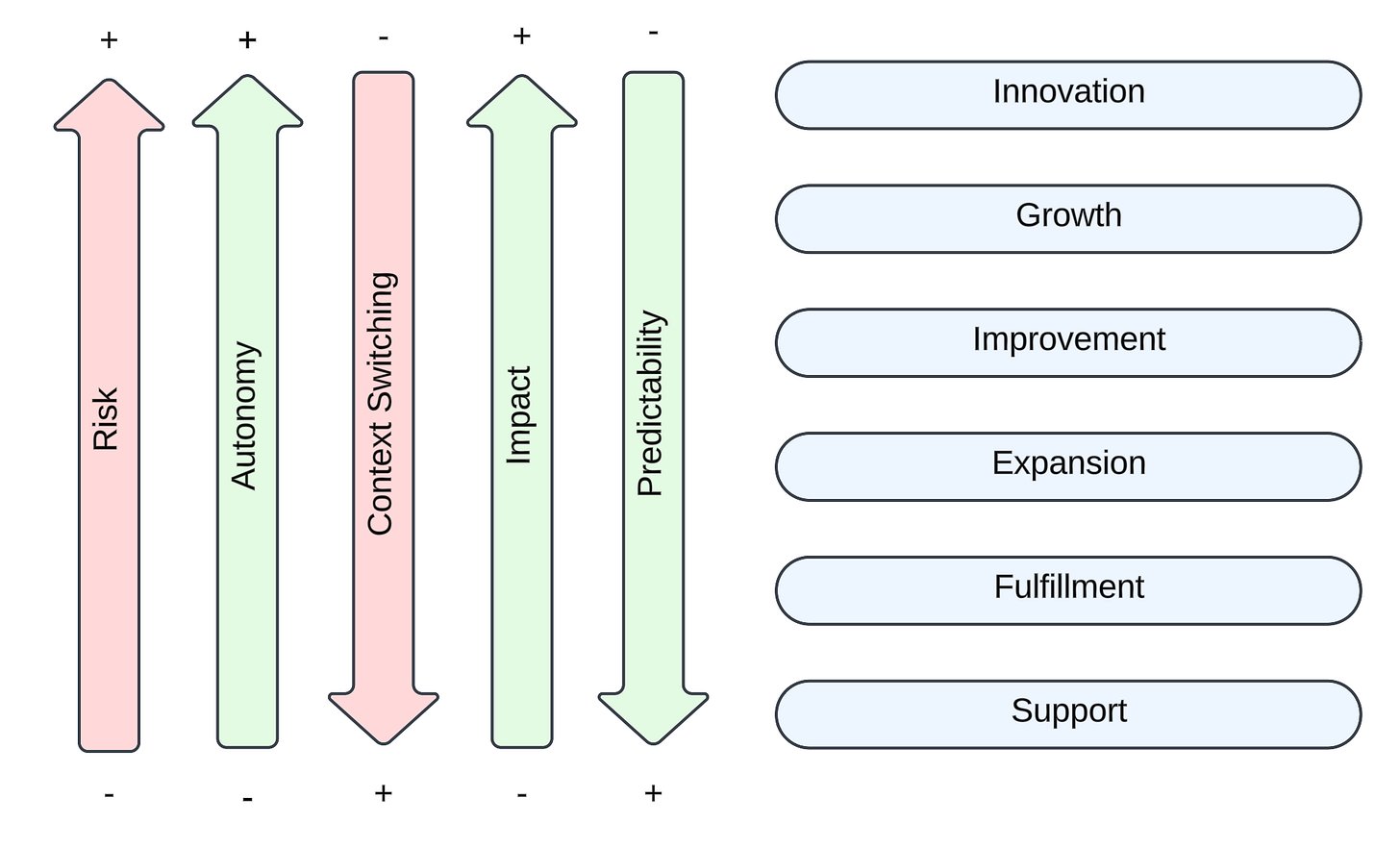

Innovation

Growth

Improvement

Expansion

Fulfillment

Support

Innovation

Innovation relates to doing things your organization hasn’t done before. Whether that’s entering a new market, building a brand new product, or standing up a new program - it requires focused efforts on items with little predictability. While you may ultimately desire to achieve a specific objective (eg. increasing revenues, building moats), the cause and effect can’t be predicted because it’s all new to the organization, nor can the actual specific steps be planned for with precision ahead of time.

Growth

This is work relates to pushing forward, or “growing” a particular outcome, usually measurable via a KPI or OKR. You might want to increase your customer retention rate by 15%, or increase a user activation funnel’s conversion rate by 10%. These are important achievements you want your organization to reach.

Improvement

If you have existing features, you’ve probably received or identified improvements you could make to them to make them all that much better. Whether that’s adding a new filter for a list, or allowing messages to be delivered by SMS as well as email. These are things that you received feedback on that you’ve identified an increment for that would provide some user value.

Expansion

A lot of product innovations can rise from seemingly unrelated technical improvements. A new way to model a user account can result in the ability to support team-based capabilities. A way to easily and quickly track aggregate data over time might be leveraged to create real-time leaderboards. This is the work of expansion - creating or expanding technical capabilities and increasing the real-estate upon which innovation can occur.

Fulfillment

Fulfillment is simple. There’s something that needs to be done by a set time. It might be mandated by contract to a customer, or regulator requirement. In any case - the work is known, the deadline is known, and it has to be slotted in an delivered precisely. The request has to be fulfilled for it to be considered successful.

Support

Support is the work that keeps the rest of the company running smoothly. Including:

defect reports

investigations or tasks for a support request

data analysis requested by another team

answering technical questions from customers or other teams

These different kinds of work are ever-present in a variety of different mixes in most product organizations.

Understanding differences in needs

It turns out different kinds of work have different needs for the people engaged in the work to be maximally effective. In fact, maximally effective might mean something completely different depending on the kind of work.

Autonomy

Context switching

Predictability

Risk

Singular impact

Core needs

On one end of the spectrum is the work of Support and Fulfillment. These are often known solutions or known problems that fit within the Iron Triangle - a combination of scope, time, and cost. These require the team to have a predictable execution tempo so that capacity can be allotted and schedule deviations can be noted early and addressed. Teams may fill quarters or years with this pre-planned work, slotting in new projects here and there, and allocating capacity to fulfilling support tickets or other minor items.

No particular work here is going to be a surprising needle mover, although if it stops operating with extreme efficiency everyone from customers to the executive team will hear about it. This is the realm of scheduled work, Gantt charts, project management, utilization, and efficiency.

Focus needs

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the work of Innovation and Growth requires freedom and autonomy by the team to explore unknown problems and novel solutions. It requires the ability to focus, for extensive lengths of time, with little ROI. Risk-adjusted paths forward may require validation of assumptions or experiments, but overall - the path forward is unknown.

A team that succeeds in Innovation can have a massive singular impact through their work - like inventing a new product or allowing an organization to shift up-market. Progress is unpredictable, and as a result the team is unlikely to be working in an environment where predictions and estimates can be made with any reasonable accuracy. You rarely see Gantt charts detailing ahead of time when inventions will be invented. Teams here need to be effective, but they are unlikely to be efficient.

That is - the pod may not be fully utilized from an execution perspective. What might be seen as a team “twiddling their thumbs” is a team having space on ensuring the things they work on are the right things at the right time in the right way.

Different kinds of work need different skills and mindsets

There’s enough differences in the spectrum of Innovation vs. Support to reveal a fundamental truth: they require very different skillsets and mindsets.

The skills needed to create extremely predictability, operationalization, and meet SLAs are things like organization, process-orientation, quality assurance, and attention-to-detail. The skills needed to create extreme innovation are things like product intuition, experimentation, responsiveness to user feedback.

They are different skills, and some can be harmful when applied to projects on the opposite end of the spectrum. Imagine attempting to create a precise and accurate Gantt chart that predicts when the results of an experiment will be achieved and whether the goal was achieved before the experiment is even run - if you could, you wouldn’t need to run the experiment!

The Core/Focus structure works because it better aligns expectations with reality

By acknowledging the different needs, we’re able to structure the organization in a way that makes it easier to align expectations for contributors and, more importantly, executives.

Contributor expectations

Contributors who prefer predictable, planned work will likely prefer working on Core pods. Contributors that prefer robust cross-functional interaction and dynamic problem solving will likely prefer Focus. There’s space for both.

Executive expectations

Executives should not expect teams operating in Core to suddenly come up with a meaningful improvement to a revenue KPI or come up with a new business line. It should be a welcome surprise if they do, but it should not be relied on, nor planned for, nor should those Core team members be held to producing such results. Executives should instead rely on the Core teams to keep the company operating as it has, smoothly and efficiently, and make space for any emergencies that occur.

Executives should not expect teams in Focus to be able to hop on to different areas every other week and still produce results. They shouldn’t expect Focus teams to be able to have schedule predictability, or to know when an innovation will occur. This is not the realm where teams should be held to estimates, or to create a six month roadmap. Teams should be allowed to freely experiment without an overly involved executive demanding justification at every step.

That’s not to say each group can’t do something outside of its area of the work type spectrum. In the event that a Fulfillment project does come to a Focus pod, or a Core pod suddenly needs to pivot on an emergency goal, executives should recognize that they might be able to do it, but they won’t be fully happy.

A Focus pod might be able to complete a fulfillment project, but the predictability and precision at which they do it may suffer. This is because fulfillment requires an entirely different set of skills than innovation or growth. They may not be experienced in breaking down work to such a granular detail ahead of time that delivery can be predicted down to the hour. Even if the work gets done, executives should not expect that it will be done to the same level of predictability, quality, or efficiency Core pod could achieve.

Likewise, a Core pod might be able to develop a brand new product, but the speed and scope may be less than desired. This is because innovation requires an entirely different set of skills than support or fulfillment. They may not be experienced in not worrying about schedule or taking risks with unknown effects. Even if the work gets done, executives should not expect that it will be done to the same level of speed, impact, or scope a Focus pod could achieve.

Let birds fly and fish swim

Fish should be judged by their ability to swim, and birds by their ability to fly. A fish not being able to fly isn’t a deficiency on the fish, nor is a bird unable to swim some issue with the bird.

This structure ultimately works because it forces an acknowledgement of the truth, that a person can’t do everything. The cost of having a person or pod be able to do everything is astronomically high, and also unlikely as the company increases focuses that require more and more depth to succeed in.

Scale-up companies have a hard time recognizing that, having come from roots where heroics saved the day, and even a single person could keep the entire system and business in their head.

The structure forces expectations to be aligned with reality.

Implementing the Core/Focus structure

Figure out if you have the problem

The first step is to figure out if your organization even has the problem this structure addresses. A good solution to the wrong problem can be more harmful than the problem itself.

A post on the internet can’t tell you whether something will work for your organization or not. You’ll have to apply the context on your own. Consider the following signals it might not be right for you when thinking through the situation you’re in.

Is your organization (or unit) too small? If you only have 10-15 engineers within your company or focused business unit , you don’t really need a structure like this. 10-15 engineers can organize as 2-4 teams, and it’s unlikely the benefits of strict segmentation will outweigh the costs of inflexibility. You don’t want an unnecessary division of labor if the benefits aren’t there.

It starts to show its benefits at the 25 - 50 engineer range, where the scope of ambition, resourcing availability, and cognitive overhead start to diverge.

Is your organization too large? If you have 100+ engineers, your organization already likely organizes in some fashion related to domains or other topology. This inherently breaks down the organization into focused enough areas where this structure may not be needed. It may be helpful for sub-parts of that organization, however - the beauty is in the potentially infinite granularity.

Is your organization already fairly focused? First of all, congratulations. If your organization has been disciplined enough to not attempt to expand into different focus areas, while still succeeding, you probably don’t need this organizational structure. This structure works best to pragmatically execute when the organization is attempting to do things that are traditionally felt as “too much”.

Is your organization a project organization? Project organizations that are primarily agency-style builders rather than stewards probably don’t need this structure. Your job is to deliver a project for the client - how it gets maintained is probably not your job. This structure is intended for organizations that have a self-developed product that they shepherd over time and are attempting to balance between keeping it stable and innovating into new areas.

Is your organization already effectively handling everything? If you have an efficient prioritization process, effective product-engineering collaboration, a reasonable processing of support and operations tasks, and have achieved a good balance between innovation and operation, you don’t need this structure. You should probably keep doing what you’re doing with the process you have set up - if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

At the end of the day, make sure your context matches. This structure works well in an startup growing from a small 10-person, do-everything team to a growing but lean business that needs to provide stability guarantees while simultaneously expanding into innovative areas. If this doesn’t describe your organization, be judicious.

Experiment in a small dose

Dramatically changing an entire organization structure is a high risk, winner-takes-all approach. It might be fast, but it’s extremely disruptive and if anything goes wrong you’ll be the first to get the boot.

Instead, start small and validate the solution works within your unique context. You, as the leader, should act as an umbrella to the teams to create the space for them to perform this experiment.

Start with Focus

First, start with a single Focus team. Remove all other distractions and give them the ability to focus. Give them guidance and empower them to truly say “no” on everything. Task them with a problem and set a 4-week time period in which the team can cook. At the end of the four weeks, check back, and see what happened and whether it worked?

What are signs it is working?

The pod has a healthy set of changes released that might address the problem.

The pod understands, measures, and monitors the impact of those changes.

The pod works together on identifying problems, defining solutions, and performing experiments.

The team made a positive impact on the problem.

If it doesn’t work, provide guidance and ensure you’ve set up the environment for success. Do you have the right mindset? Did they have the right clarity? Did they have the right skills?

Then, try a Core team.

Second, assign a team to work as if they were a Core team.

It’s more likely than not that your Pod is already running in some variant of a Core where a team’s roadmap has to be balanced across many different things.

Take one of those teams and set expectations that they aren’t expected to move the needle on a KPI, and have them own their roadmap and schedule for the next 6-9 weeks.

Their only outcome is to achieve balance and predictability and meet their commitment. They can ease off the throttle and not have to pivot to address things reactively. They don’t have to worry about trying to push forward a metric or KPI outcome while balancing stability, intake, and operational support.

Their one job would be to set a roadmap and meet it.

Afterwards, evaluate: did either work, did neither work, did one work but not the other?

Scale the experiment

If you’re seeing positive results, expand the concept team by team.

Over time, you’ll formalize the Core/Focus split internally, and your organization will be happier for it. If it’s working, this ultimately means you have organizational buy-in and don’t really need to “sell” it.

Watch out for the messy middle

You may be left with a couple of teams that seem to be more “miscellaneous” in nature, or are still acting as something not quite Core or Focus. This is the messy middle of the transition, and you should do your best to figure out how to adjust the structure, intake, and prioritization to better align the work structure and the team.

Rotation approaches help (eg. one team focuses on a particular area, then switches off to act more like Core) in situations where you can’t quite say “no” to the work.

Over time, as long as you’re tracking future commitments and aligning them towards Focus or Core availability / capacity rather than looking at them as interchangeable, the burden should reduce.

Obtain executive buy-in

You can use this structure without buy-in from other executives, but it becomes much easier if the whole executive team is aligned with the approach - you spend less time putting your own neck on the line and arguing, and more time being effective.

Every executive team is different, but you should generally be prepared with data and narratives. You should have at your fingertips:

The past 1-2 years of development and delivery performance, to demonstrate the impact on performance and results

Suggested metrics: deployment frequency, PR throughput, list of feature and product releases, user and customer sentiment, outcomes achieved, success or failure of initiatives, etc.

The past 1-2 years of investment allocation, broken out by team and team size, to demonstrate the lack of focus

Suggested metrics: # of projects per team per month, average and median lead times, issue counts, issue type breakdowns

Qualitative feedback from the team

What’s your narrative? It really depends on what your metrics say, but if you’re even reading this, you’ll like have encountered:

Too many different simultaneous pursuits negatively impacting effectiveness, success outcomes, and morale

Increased defect rates, or a litany of avoidable simple “unforced errors” that are par for the course on a distracted team

A lack of predictability resulting in stability issues or operational misses

A lack of effectiveness resulting in slower delivery or non-impactful busy-work

A lack of iteration leading to incomplete projects, loss of responsiveness to user feedback, and breadth of product scope that lacks depth and cohesion.

If it turns out you don’t have data that aligns with the issues above - pause. Truly think about whether you are experiencing this problem and that it warrants a solution like this.

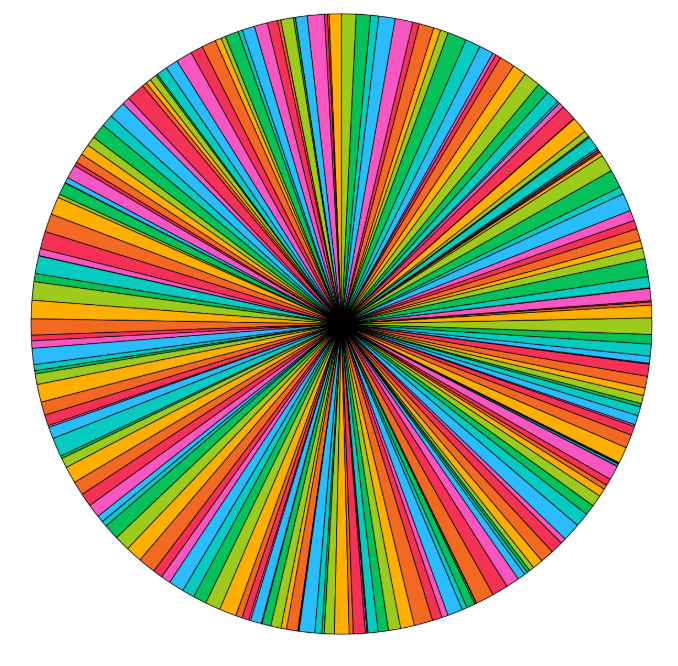

Whatever data you have, show it visually.

It’s one thing to say “we worked on 200 projects this year”. It’s another thing entirely to show a pie chart with 200 slices, and a headline saying that only six days were spent on average on any given project. Can a team realistically be expected to create amazing, innovative products if they only spend 6 days on any one product?

Aim for these two points

Your two key buy-in points you want to achieve:

Acknowledgement from executives that there is too much being done at once

This means that the executives become more disciplined in not committing to major new areas without considering resourcing.

Acknowledgement from executives to respect the resource split

This means that if a new initiative begins, a team must be available to work on it instead of expecting a team already working on another thing to work on it simultaneously.

Once you have it, it’s all on you to set the Core/Focus structure up for success.

Set it up for success

Think about who leads Core

For Core, you want leaders who can keep the trains running on time.

Planning, projection, orchestration, scheduling and organizational skills are key. You want detail-focused predictability creators. Capable of prioritizing and sequencing work in a way that results in the most efficient and stable execution.

The leader should excel at communication to other internal stakeholders. They' are the ones that will set the tempo and keep the organization in the loop, providing stability. They’ll need to set a sustainable, steady, somewhat slow pace.

Think about who leads Focus

For Focus, you want leaders who have high imagination and the ability to iterate to get to their desired goal.

These are your problem solvers. They shouldn’t be burdened by bureaucracy, or bothered by a desire to achieve perfect. For them, good enough should be good enough. They are the ones that can make highly effective trade-off decisions, knowing what to keep and what to cut.

The Focus teams work best filled with excellent collaborators who prefer working in real-time to solve the problem together.

Try to keep it stable

The entire premise of this structure is teams work best when they can be stable. However, sometimes you may need to move teams or people from one group or another to support major business changes.

This happens, but try to do so sparingly. As much as possible, let Focus teams focus and be effective, and let Core teams stabilize and create predictability.

Don’t be overly rigid

Sometimes your Core pods will find time and desire to work on something a bit more innovative or experimental. Other times, your Focus pods will find an operational irritation that they want to fix.

That’s OK - as long as these things don’t distract them and are, as much as possible, voluntary from the Pod’s perspective. The structure is not intended to be a prison for the contributors, but a tool for expectation management.

Working with executives using this structure

Acknowledge it requires executive discipline

Executives can easily cross boundaries and create exceptions that ultimately dismantle or render this structure ineffective. It’s important to remind people that the structure only works if the constraints of the structure regarding expectations are respected.

Align on an allocation approach

I’ve found it best when executives make their investments based on allocations. How much money and time they want to invest in solving a problem.

Executive interests vary, from pushing forward a metric, to creating a specific feature, to solving a particular problem. It’s often difficult to get everyone on an executive team to think at the level of a goal or problem. If you can do so, congratulations - you are a better executive whisperer than I.

I personally prefer an approach that allows for a bit more pragmatism to support a transition from specifying particular features to thinking about more broader investment categories.

Try not to get tied into specific projects - you can set a limit if you prefer. Instead, guide folks

towards “problem areas” or “goals" they want to achieve to secure autonomy for your teams.

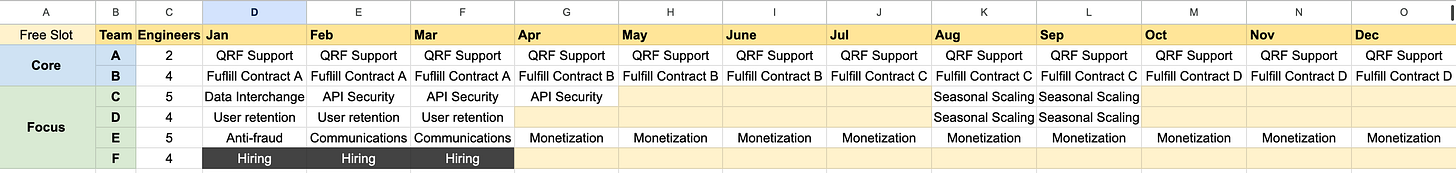

Visualize capacity and focus with boxes

I prefer a simple “box” approach - it’s both easy to understand and helps illustrate the availability of chips. It aligns well with the Core/Focus structure.

When a new executive “thing” needs to be done, it helps to have everyone look at the box and ask “when and where does it fit?”

If a box already has an entry in it, the following conversation is then clear: “are we willing to drop this thing we were already going to do?”.

If there are no boxes left - congratulations, you are 100% allocated. Unless new capacity is built, or we can tolerate lower delivery and capability by shifting people around, the items cannot be worked on by the organization according to its current state and roadmap. It’s as clear as day.

You’ll have to guide people in the conversation - push back on attempts to assign specific individuals to projects (development is a team sport). Guide people against the ever tempting allure of having a Core pod do it.

Remember: you’re the first line of defense against the structure being eroded.

Pro-actively report results

You can’t just create a major structure change, and then completely forget it exists.

Organizational change management requires reporting of results, and regular evaluation of whether the structure and process are still suitable and working as intended.

Pro-active provide reports of trends in the areas the team cares about - effectiveness, efficiency, impact, morale. The metrics you shared to justify the structure change should also be tracked after it’s been implemented. A cadence of once a quarter can be a good start.

Parting thoughts

Startups have to both survive and thrive, while growing multiplicatively. It often means the structure needs to change to support the new phase of the business. Ensuring that expectations and capability are aligned from the contributor up to the executive can help ensure continued effectiveness and achieve organizational balance in stability and innovation.

Be judicious. If this structure works for you - excellent! If not, don’t be afraid to throw it out and try something else that better fits your context.