Making decisions - When does your Startup Needs Engineering Managers?

Understand how startups evolve, why managers are needed, and how to figure out if you need to hire an engineering manager.

Most tech leaders who have been in an early-stage startup have encountered this question: “Do I need an engineering manager?”

It’s a tough decision. Most early-stage startups aren’t flush with cash. Every dollar they spend on an “expensive” manager is one less dollar they can spend on a direct contributor to the codebase.

Furthermore, hiring the wrong manager can be incredibly damaging to the culture and organization. Tech leaders in first-time leadership positions have it doubly bad — they also have to wrestle with the fact that they have never hired a manager before, increasing their likelihood of hiring a bad one.

Faced with such uncertainty, many startup tech leaders put off the decision, falling back on what they know best: individual contribution.

Sometimes later is too late

Yes, a management hire too soon can become an unnecessary expense at a cash-strapped company. However, the flip-side is also true: a hire made too late can end up costing the company dearly. Cultural, technology, and process issues compound over time and even the world’s best managers can’t undo the damage overnight. Timing is incredibly important.

How do you determine when you need an engineering management layer?

I’m going to spoil the ending early — a blog post online can’t tell you when your company needs managers.

It’s a highly circumstantial decision only people at the company will have the context to make. The best an online article can do is to help arm you with knowledge — an understanding of the fundamental “Why?” behind managers so that you’ll be better informed to determine the “When?”.

Understanding the evolution of the engineering organization

To understand why one would even need an engineering manager, it’s important to understand the lifecycle of an engineering organization within a startup, which can take place over a period of years.

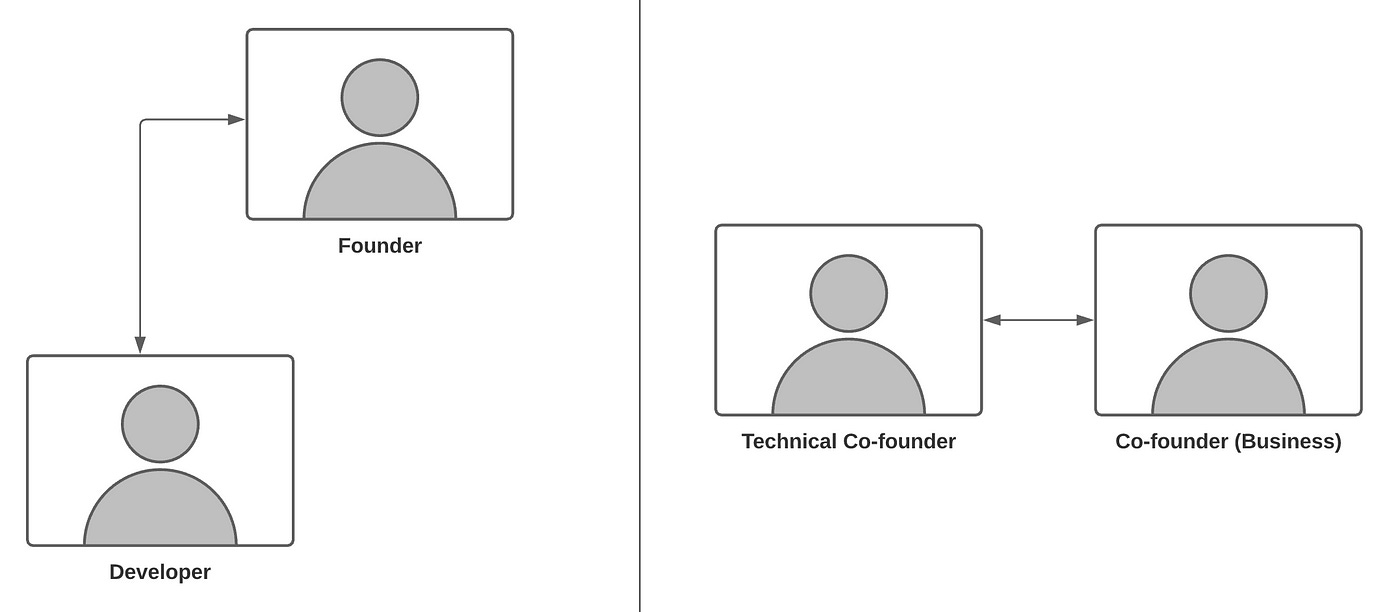

The beginnings

Startups typically begin life with a single in-house developer or a contractor. You couldn’t even call it a team at this point. This initial developer either either reports directly to the founder or is themselves the technical founder.

Bringing product to market

As the company sells their vision and what they’ve built so far, they have to increase their development speed to build all of the things the market demands. They reach the point where contractors are not enough or get too pricey.

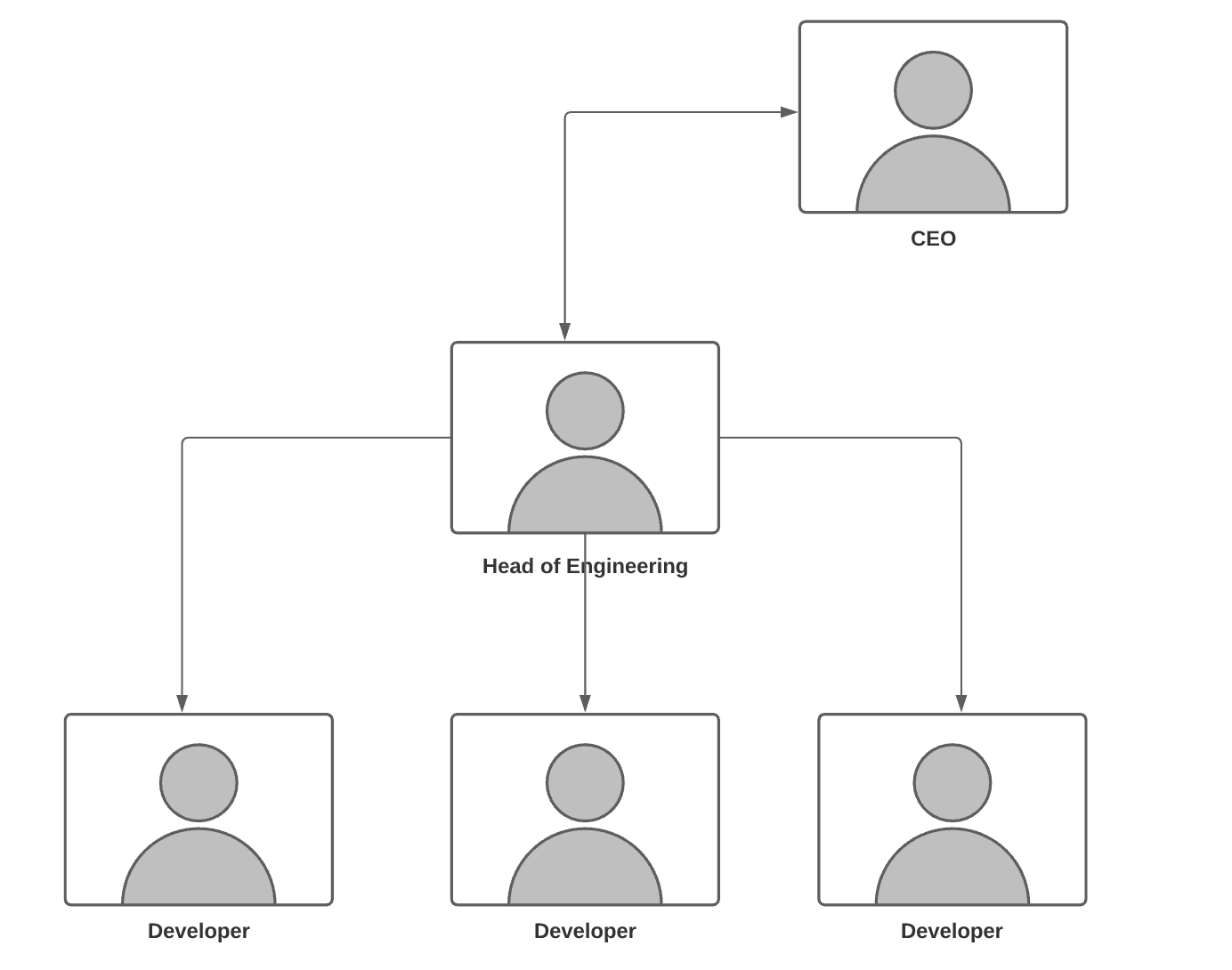

To support the new demands on the development team, the hiring strategy shifts, and the focus starts to be on building an in-house team. The startup will eventually reach a point where there’s 6–8 engineers in a single team all working on the same product.

With a team this large, the founder is no longer in a position to directly manage these engineers, if they ever were in the first place. They’re too busy making deals, figuring out finances, business plans, and all of that stuff that business people do that engineers often take for granted.

Instead, the responsibility of ensuring the team still executes quickly falls to the initial developer or the senior-most developer. This developer, through acquisition of a vast amount of domain knowledge over several years, has become the de-facto Head of Engineering, in charge of all of the other engineers that are brought on.

Their title differs depending on the company — some companies use Director of Engineering, others CTO, still others Lead Software Engineer. The technicality doesn’t matter so much as the fact that they are the technical leader of the organization.

The burden of success

As the company grows and gains traction in the market, the tech demands increase. Cross-functional collaboration is more and more a key component of the job. Working with business stakeholders, potential customers, regulators all while keeping the product team rowing is a lot of work and a lot of communication.

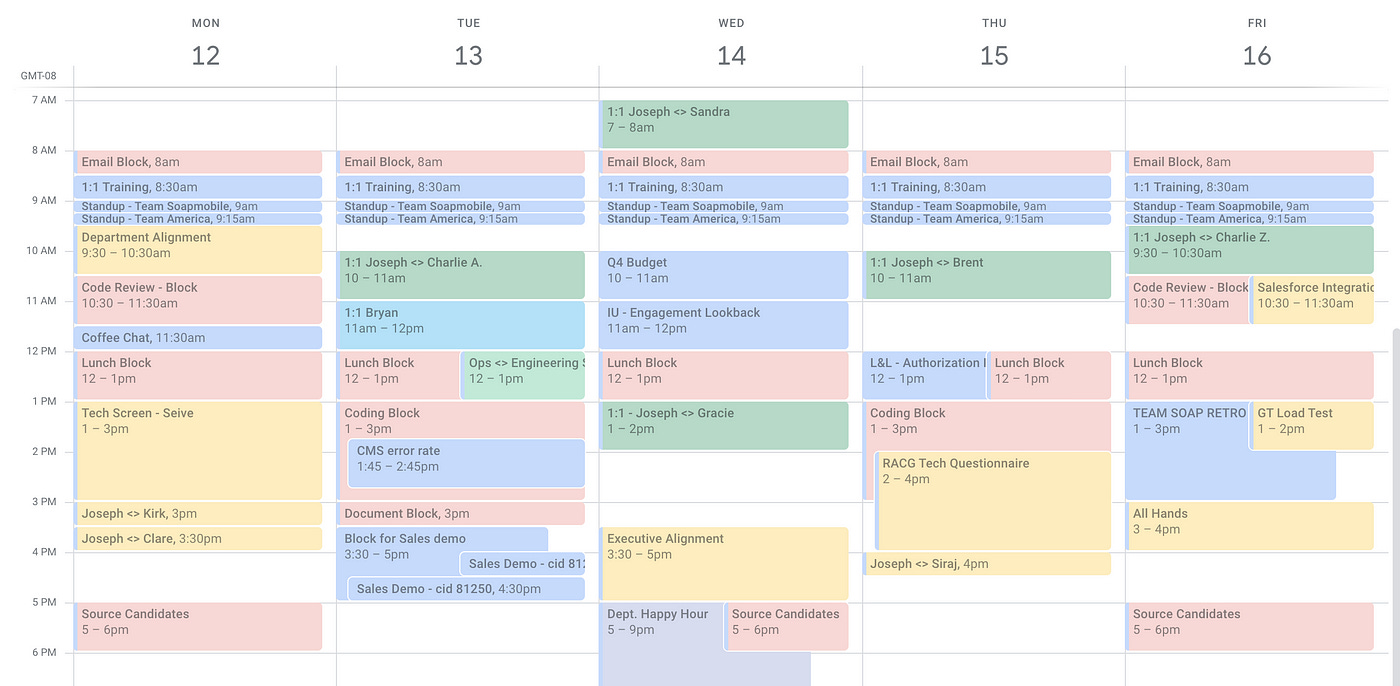

At some point, it dawns on the Head of Engineering that their time is no longer their time. A mere glance at their calendar evidences this:

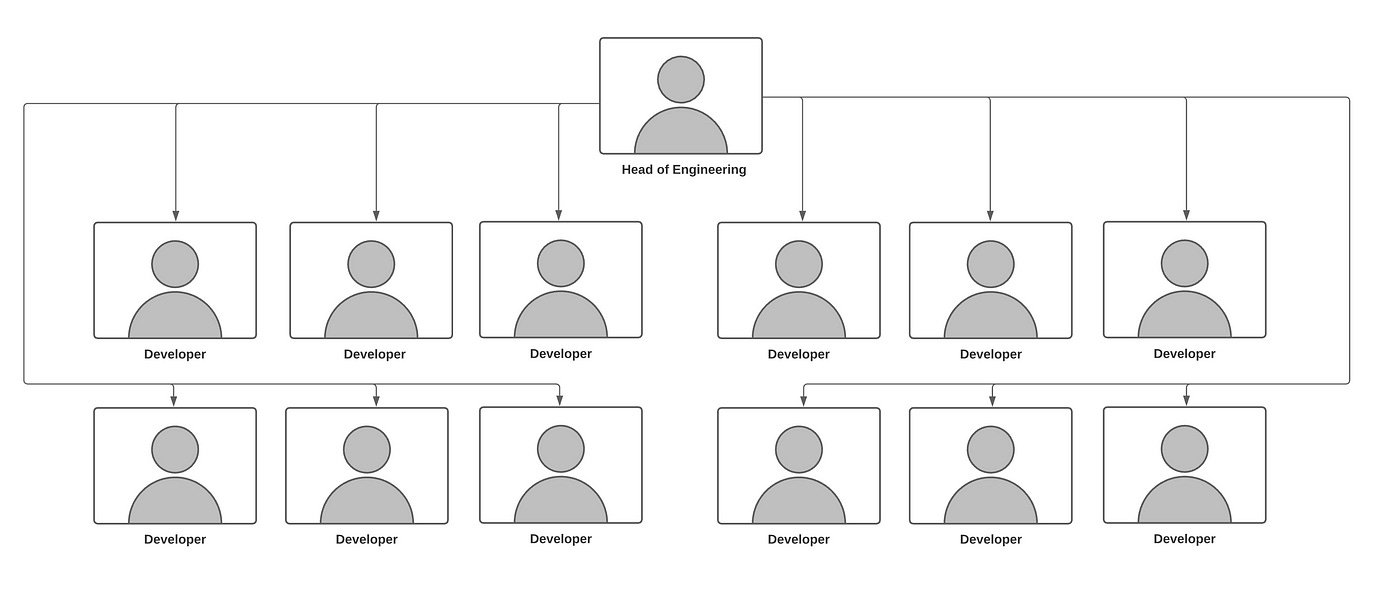

Somewhere along the line, their time went from coding 24/7 to meetings 24/7. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when that was, but it was probably when the Org Chart started looking like this:

More people necessitates more communication. Projects get more complex, with more moving parts. Business demands increase as the company’s growth accelerates. Leadership desires the Head of Engineering to focus on the most important thing. With this many people, the Head of Engineering can barely focus on anything.

Bringing on senior talent

If the organization doesn’t have any senior engineers at this point, they often bring them in, with the rationale being that senior engineers require less management and can help pick up some of those responsibilities.

This is a coincidentally correct rationale. As these senior engineers become reliable executors, the Head of Engineering may start to delegate responsibility for completing certain projects or streams of work to them.

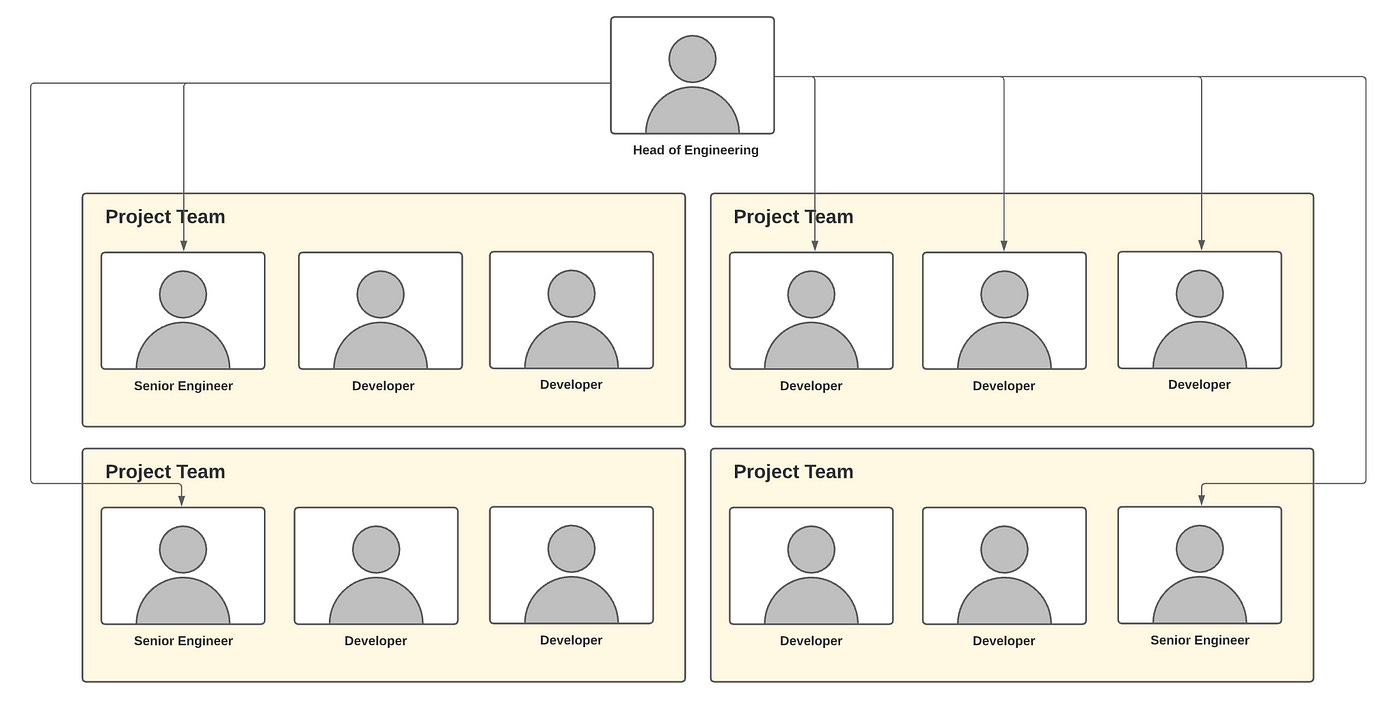

Splitting into teams

In many cases, the Head of Engineering implicitly knows when they’re reaching their limits.

They often try to save more of their own time by only syncing with the senior engineer that they put in charge of the project or workflow, avoiding having to sync with every individual engineer that is part of the same project.

This makes sense — part of the incentive of delegation is for the Head of Engineering to spend less time on certain things, which includes project and people oversight, and this activity reduces the number of communication channels the Head of Engineering needs to keep synchronized.

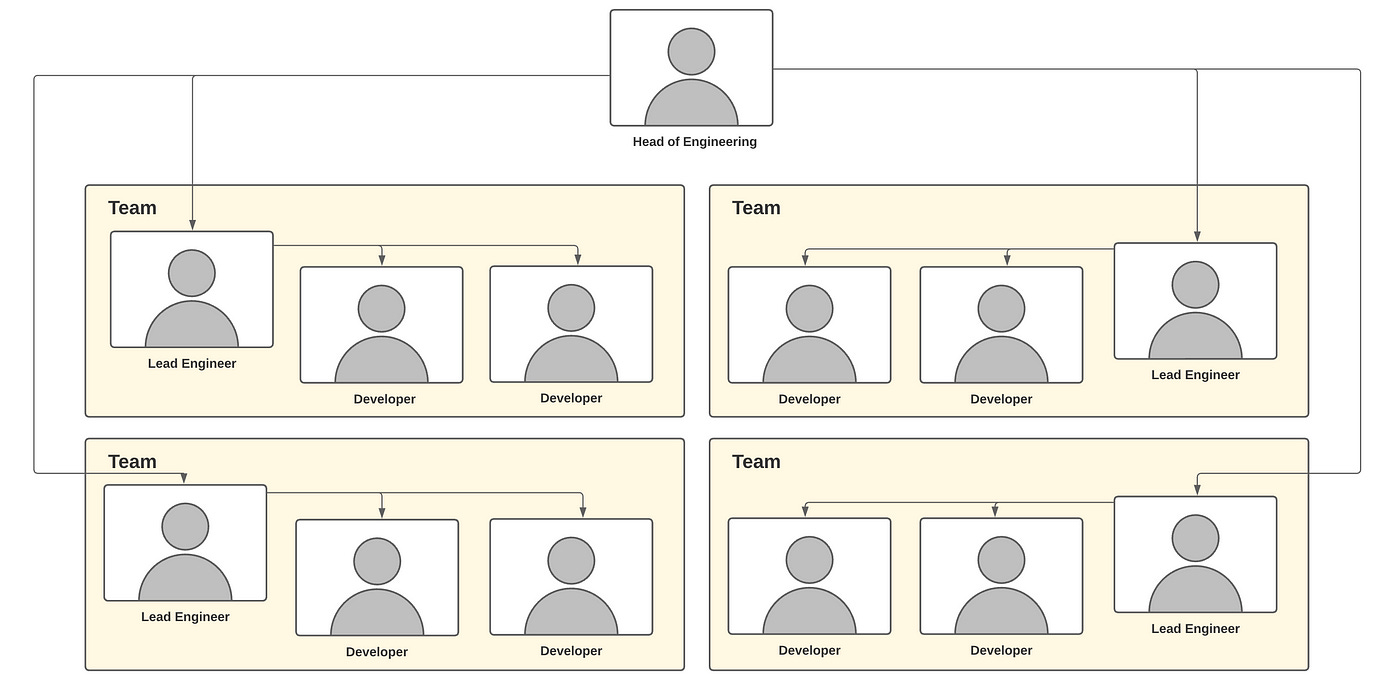

While formal reporting lines don’t change, the Engineering organization chart starts to implicitly look like below:

Formalizing the split

Eventually, the split gets formalized. As I wrote about in another post, there are a variety of ways you can split teams out, with pros and cons to each structure. There’s also hidden dangers of having skilled ICs suddenly jump into management roles without proper preparation, and methods with which to counter the drawbacks.

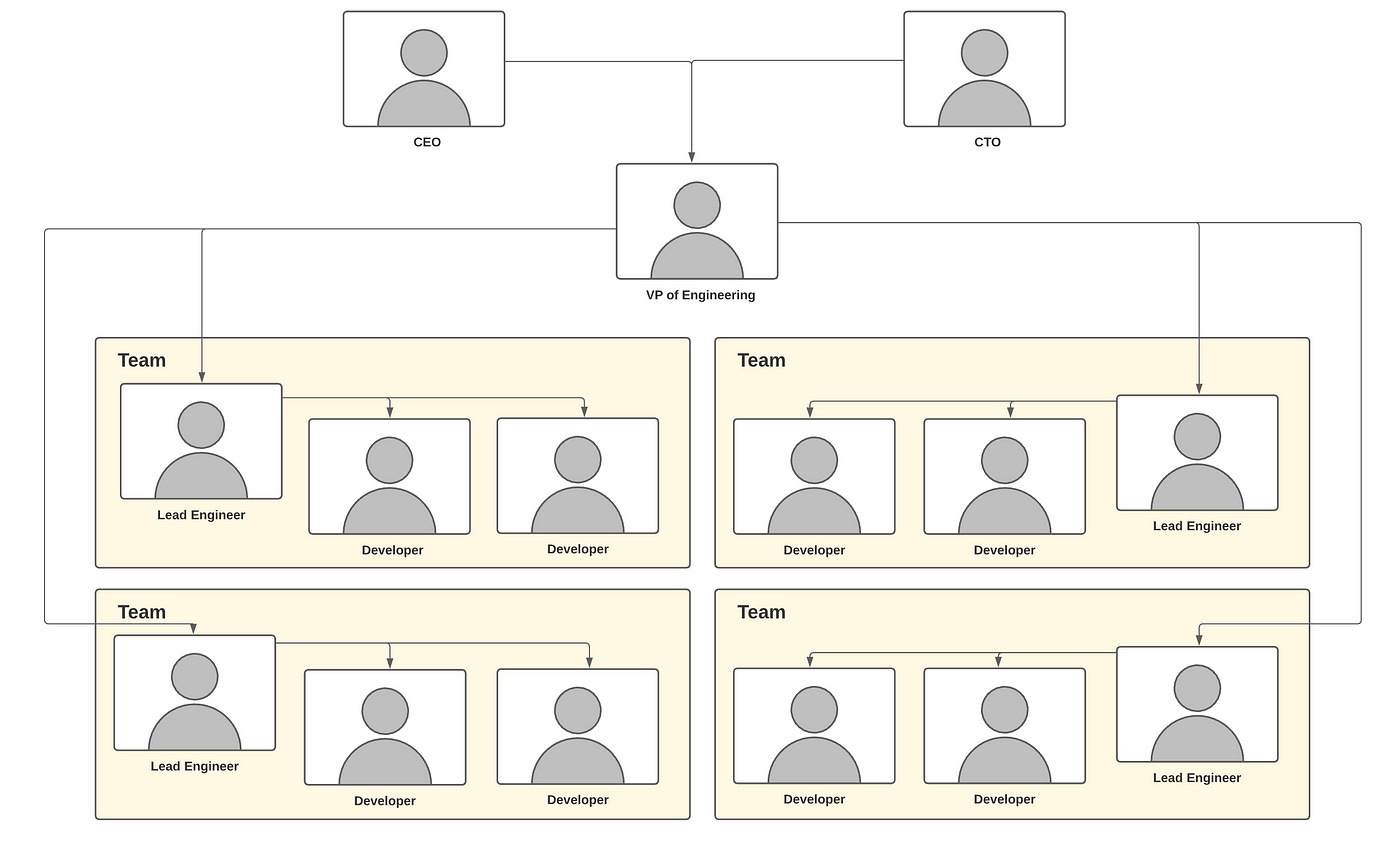

Regardless, the final end result is that there are different teams, with different individuals responsible for them:

Things under this structure become much more manageable for the Head of Engineering, and organizations can go a long way with this approach.

Why does this work?

There’s some fundamentals to organizational structures at play in this scenario that we need to understand..

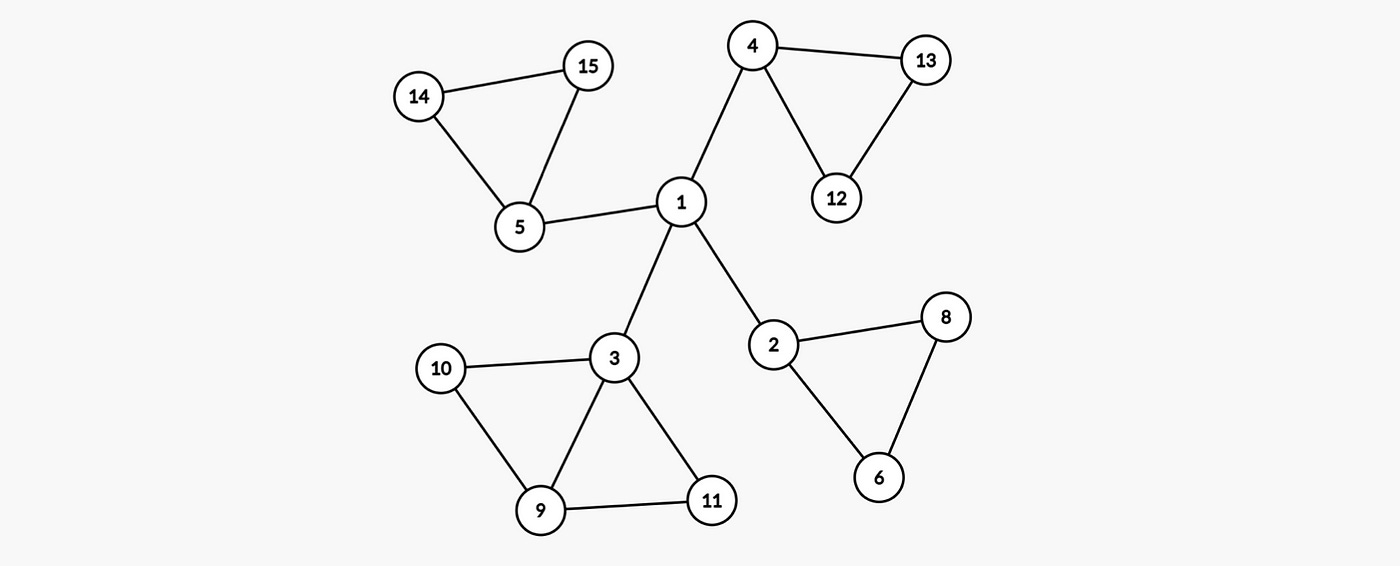

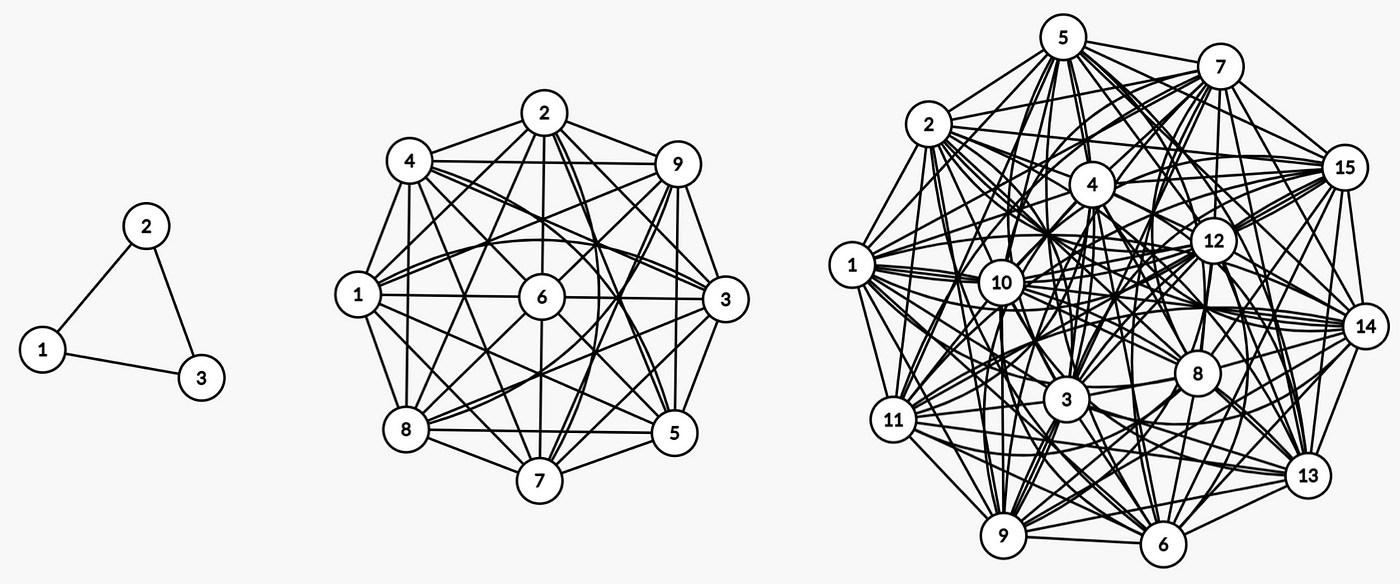

As the organization grows, it becomes more and more difficult to ensure everyone is in-sync. This is because communication channel requirements scale exponentially with the size of the organization.

In early stages of a startup, say — when there’s just three people — it’s easy for those three people to talk to each other. There’s only three communication pathways to achieve shared consciousness and align. Everyone can communicate with everyone.

But if the organization gets bigger? That’s another story.

What we’ve got here is failure to communicate

As the number of people increases, the number of connections between them explodes dramatically. A synchronization strategy that used to keep 5 or 10 people in sync suddenly breaks down at 15. The problem gets even worse as the organization grows:

9 people? 36 connections.

15 people? 105 connections.

50 people? 1,225 connections.

100 people? 4,950 connections.

It’s impossible to keep that many people synchronized and on the same page by using a strategy that involves 1:1, direct communication.

This is a big reason why organizational structures exist: to create a flow of communication that can be managed effectively. Transitioning to a model where communication flows between specific individuals creates order.

There are some minor drawbacks, however. Because every individual member of now does not have access to the full consciousness of the organization, it has the tendency to create silos. These silos can easily become misaligned with the larger organization.

These drawbacks are countered with a focus on effective alignment, generated by — you guessed it — effective management activities. These management activities ensure information flows to where it is needed and individual silos are putting their efforts in a direction that aligns with the rest of the organization.

Why can’t the Head of Engineering do it?

A common question I get asked is — why can’t the Head of Engineering just manage people?

They could, if they have the skillset (which many do not), but it only delays the inevitable. There’s just too many other demands on their time for them to effectively do everything they are asked to do at a growing organization.

Companies recognize this, and most eventually split the responsibilities of the role of Head of Engineering.

Splitting the Role of Head of Engineering

The Head of Engineering at this point has (or doesn’t have) certain skills.

If we use a simplistic 4-quadrant model of a CTO skillset, we get the following:

People management

Execution management

Coding and Technology

Governance and Strategy

Few, if any, people are strong in ALL of these areas. Most engineering leaders have one or two of these areas they excel at, and have varying levels of performance and interest in the others.

By having someone that excels in the areas the Head of Engineering is only acceptable at, organizations can ensure key aspects of the role get the attention they deserve. It allows the Head of Engineering to focus on their strengths, and the organization as a whole gets stronger.

Sometimes, this is a tough pill to swallow, and some technical leaders push back against the idea of letting go of their authority and power. They cling to all of these areas regardless of their skills, weakening the organization to the benefit of their ego.

However, effective leaders recognize the importance of leaning into their strengths and welcome the ability to focus that comes with splitting their role.

Where do the responsibilities split?

This is highly context-dependent and really depends on the people involved and the organization.

A Head of Engineering with people management and execution management will likely want to be in a role that stays close to the day-to-day, and pass off strategy and governance to an incoming CTO. In cases like this, the Head of Engineering becomes the VP of Engineering.

A Head of Engineering who want to focus more on the coding, technology, and infrastructure aspects of the role essentially can take on the the role of Chief Technologist. In cases like this, they often remain an IC-focused CTO, with execution management falling to a new VP of Engineering.

Perhaps the Head of Engineering wants to be more external facing / governance / strategy-oriented. In this case, they remain a governance / strategic CTO, with management of execution falls to the VP of Engineering.

The organization should work with their Head of Engineering to find their strengths and ensure the role breakdown fits their interests.

What happens if the Head of Engineering isn’t ready at all?

Of course, there’s always a final option: the Head of Engineering simply doesn’t have the skillsets required to take the company through the next level.

There’s numerous reasons why this can happen.

Some engineers start their careers at a startup and grow with it. In the early stages where building is the priority, they can effectively perform the role, but later stages have significantly different skill requirements that they may not be ready for.

Some simply aren’t interested in the actual responsibilities that go along with the role once the organization gets larger, and it just wasn’t quite what they expected.

Organizational requirements change as a startup moves from stage to stage, and different skills are needed for different phases. Although many do, not everyone does adapt to these changes and keep their skills relevant. It’s not universally interesting to everyone, and people may have preferences for specific startup stages.

The solution here is straightforward: they either take on a lower role in the organization more suited to their skillsets so they can continue contributing maximally, or they part ways with the company.

The Manager of Managers

Of course, I assume you’re a lucky organization blessed with a fantastic technical leader.

Whatever the role split looks like, the VP of Engineering eventually takes over the management of the development teams, managing the managers who manage the teams. Sometimes they report to the CTO, other times they report to the CEO.

The management layer has been installed, and as the team grows it expands over time, including more Managers. For larger organizations, the Director of Engineering title often makes a comeback in a reduced, non-organizational scope, managing Managers that are part of a specific work group or department.

What do you need to ask yourself?

So, now that we’ve examined the evolution of this hypothetical startup, we come to the real question: how do you tell when it is time to get a management layer for YOUR startup?

Truthfully, a blog article online can’t tell you that. It’s context-dependent. However, by asking yourself the following questions, you’ll build up awareness of what specifically to look for:

Does your organizational culture appreciate management?

Some startup cultures are very IC (individual contributor) centric to the extreme. Early-stage startups survive because of the willingness of its members to do whatever it takes, wear as many hats as possible, and grind and hustle to get things done.

In these organizations, the concept of someone who sits around not actually doing anything themselves is anathema to the idea of the Heroic Contributor. It’s a misguided belief, to be sure, but one that I found to be prevalent in many early-stage startups.

If your organization doesn’t appreciate managers, it will place the expectations of an individual contributor on them and diminish the appreciation for the management aspects of the role, and that is a recipe for failure.

What do you do if your culture doesn’t appreciate managers?

If your culture doesn’t appreciate managers, it probably either:

Has had bad examples of managers

Don’t actually know what the value of a manager is

Managers exist for a reason and their actions can contribute greatly to even execution-oriented cultures— coordination, information pumping, alignment, are all activities that reduce execution friction across an entire team.

Managers can also ensure skills and career progression, providing valuable focus on training and growth. These aid in execution, and also retention of employees.

Finally, Managers can help ensure empiricism and improve processes over the long-term through the collection of metrics and optimization activities based on them. A focus on improving can help remove inefficiencies and ineffective behaviors — things that are hard to focus on if you’re also busy trying to do you part in the next project.

Management activities (done well) act as force multipliers, leading to the dreaded business word of synergy, the sum of the parts together becoming greater than what they could be individually.

Finally, remember: Google once tried to get rid of all of their managers. It went quite poorly.

Is your Head of Engineering overwhelmed?

Overwhelmed can be an overloaded term, so let’s specify what that means.

Does your Head of Engineering…

…spend more time doing things they dislike than they do things that they love and excel at?

…seem to be in meetings all day and have a massive backlog of code they need to write?

…appear stressed, anxious, demotivated, burned out, depressed, hopeless?

…keep asking for budget to hire senior engineers in hopes that they free up time?

If the answer is “yes”, you should look into it further.

Do projects frequently miss release targets?

Projects that get delayed repeatedly indicate some form of process, quality, or people issue. The fact that they frequently happen means that there’s something missing, whether that be better coordination, clarity on goals, or time to account for technical debt.

Managers can dive deep into these issues and help keep projects on track.

Are you getting a lot of bugs?

Here’s a secret: in well-engineered projects, bugs should happen LESS frequently over time, not more. If bugs happen more and more often, it can be indicative of severe quality issues caused by technical debt, unrealistic deadlines, lack of skill, or quality standards that are tending lower.

It’s easy to dismiss an increasing bug count as “the project is getting more complex” or “we’re moving fast and breaking things” but the truth of the matter is that if you have the option of “moving fast and not breaking things”, then “moving fast and breaking things” is irresponsible.

Do engineers feel out of sync, lacking clarity, or misaligned?

One of the key management and leadership activities is providing clarity to the team. Good managers can act as information pumps, ensuring people have the information they need to make effective decisions aligned with the goals of the company. They act as alignment generators that keep everyone on the team rowing in the same direction.

If your team doesn’t seem to know what’s happening, or seem confused as to the goals or current situation, it’s a sign that they’re not getting the information they need.

Employee surveys can help sniff this out, along with 1:1s and other tools.

Do engineers complain about a lack of skills or career progression?

A good manager can do wonders for the career progression of an engineer.

They have the time to provide resources, direction, coaching, training, and opportunities for the engineer to grow and improve. They can work 1:1 with the engineer to develop a personalized growth plan that helps the at a rate far more rapidly than they could themselves.

It’s a massive retention tool and competency booster long-term. However, it requires focus and attention, and is often the first thing that gets dropped when deadlines start getting missed.

Without a management layer dedicated to this, it’s often hit-or-miss whether the need gets fulfilled.

Do you have no visibility into engineering performance or trends?

Agile-istas often decry the use of metrics to measure performance of a development team, instead preferring to point to “working software” as the main measure of progress and success.

In an age where anyone and their dog can create working software, is that really a good standard to use?

While I agree metrics such as Story Points and Velocity have been abused by misinformed business leaders, proper use of metrics can be a powerful signal to indicate process issues or engineer capability growth over time.

Metrics like Cycle Time, Change Failure Rate, Deployment Frequency can help provide insight into whether your team over the long-term is getting better or worse, and you can target improvements to focus on areas that will benefit the most from them.

Do engineers feel powerless?

You can tell when you’re on an empowered engineering team. From the moment you start working with them, you feel this hum of work and this desire to excel and improve everything.

You can also tell when you’re on a disenfranchised engineering team. They don’t communicate. They don’t take the initiative. They do only what they are told to do — no more, no less. They don’t enjoy the work.

Effective engineering management can revitalize a team and help inspire and empower them. I’ve seen tenfold improvements in development effectiveness on teams that have been placed under an effective manager after languishing under a bad one or no manager at all.

Hiring a manager isn’t an easy decision, but it is a critical one for a startup. As startups grow and evolve, the collaboration burden gets too much for the Head of Engineering to exclusively bear.

An effective management layer often becomes a necessity to ensure the organization can continue to succeed and excel to the next level.