Making decisions - When should you trade off between speed vs. quality?

Startups develop rapidly by applying different kinds of shortcuts — learn what they are and know when to take them yourself.

Startups survive because of their agility and speed — their ability to pivot and move quickly. They measure their execution tempo in hours, days, and weeks. This allows them to maneuver around larger lumbering organizations that operate in tempos of months, quarters, and even years.

In environments like this, speed is king. Rapid time-to-market is the startup’s competitive advantage. Without it, you can’t get the tight feedback cycles that make iteration possible.

Achieving these speeds isn’t easy — it requires startup engineers to make a lot of sacrifices (both personal and technical) and take plenty of shortcuts. These actions have pros and cons that impact the organization’s ability to sustain and maximize its speeds over the short and long-term.

Two kinds of shortcuts

There are two kinds of shortcuts engineers at startups make in the pursuit of speed:

They reduce Quality

They reduce Scope

Reducing quality

Reducing quality means writing code quickly, without regard to the general hallmarks of maintainability including:

Correctness

Cleanliness

Understandability

Engineers taking this shortcut choose not to do things that would otherwise ensure these attributes, such as:

Writing automated tests

Refactoring

Creating abstractions and thoughtful system designs

Generalizing repeated functionality into reusable libraries and frameworks

Not doing these things saves engineers time in the short-term. They prioritize the speed-to-create, which allows for faster short-term releases at the expense of speed-to-change, which slows down future changes such as integration, debugging, and iteration.

Reducing scope

Reducing scope is a shortcut engineers can take regarding completeness and comprehensiveness. Activities that fall into this are often product-related, which requires negotiation with product owners or thoughtful execution management on the part of engineers.

They include:

Not building all of the capabilities that are envisioned

Not building everything at once

Not integrating with existing process or technology

Not addresses all of the concerns (eg. scalability, measurability, security)

Not involving engineering at all (eg. doing things manually)

Not automating or operationalizing (aka. doing things that don’t scale)

Not handling less common use-cases

While many of these aren’t entirely up to the engineer to decide, engineers can influence these decisions. At early-stage startups, the order in which to actually execute is often up to the engineer to figure out, as they have to lay the track needed to get to the eventual goal. It is here they can influence the build by developing smaller, complete, fully-functional verticals instead of building the entire feature all at once.

Which one to pursue

While both of these practices can result in speed, only one results in speed over the long-term.

Sacrificing quality can be a massive initial speed gain during the first creation of the product, but these speeds rarely sustain themselves once iteration starts to occur — and iteration will occur.

Maintaining is harder than creating

Teams that sacrifice quality slow down over time, becoming overburdened by bugs, untraceable issues, and difficult-to-change systems. Because they optimized for creation instead of maintenance, which makes up the bulk of software development activities, the team’s output slows down to a crawl after the initial build-out.

The only solution for teams following this strategy is to approach everything as net-new — building things separate so they don’t have to deal with the debt they’ve created.

This means that products end up as shallow and unintegrated silos, regardless of whether they’ve been built before. Teams that operate in this model can’t take advantage of development momentum because they’re creating net-new on everything each time.

This works in contexts where exploration and experimentation is still the name of the game, but not in situations where product-market fit has been discovered and needs to be capitalized on.

Fixing quality shortcuts costs money

Resolving issues caused by quality shortcuts costs the startup a lot of money. More engineering headcount is required to push through the issues, or higher engineering salaries are required to get the skill needed to resolve the issues. An engineering team of 4 can perform incredibly well in a high-quality environment, but you’d need a team of 12 to reach the same amount of effectiveness in a low-quality one.

The alternative to throwing money at the problem is not something many startups can bear: pausing feature development to spend time fixing issues or paying down technical debt is the last thing founders want to do.

Either way, there’s a significant cost to quality shortcuts and they have to be meticulously measured and applied.

This strategy can be appropriate if your organization is aiming to receive a massive investment round to push through the problems, but if that’s not in the cards you’re better served to take the other kinds of shortcut.

Where possible, reduce scope instead of quality

Prefer reducing scope instead of quality. This will help ensure speed across a longer time-frame. Yes, it does mean that you’ll need more skilled engineers initially, but the payoff is massive.

One secret benefit to prioritizing quality — if you sustain a certain level of quality over a long enough period, you’ll eventually reach a point where development starts to speed up, not slow down. This is because higher quality code leads to higher confidence in development and maintenance, which results in faster changes.

Change = Risk

Lack of confidence is the number one speed killer. If a developer is not confident that their code will work, that they covered all the edge cases, that they fully understand what is happening, or that they won’t break anything, they will move slower to compensate.

This is because risk increases as change increases. While a static system only has to deal with environmental risk (risks that occur from not changing), a system under active development has to deal with much more risk — risk of bugs, risk of failure, risk of edge cases, risk of losing customers, etc.

You combat risk by minimizing the negative impact of failures and improving quality so that developers have increased confidence that the changes they are making are correct and have no unintended consequences.

The more confident a developer is in the change they are making, the faster they move. By keeping quality higher, you improve developer confidence and thus improve speed.

Advice for the real world

Of course, we live in the real world where things get messy and the lines are easily blurred. Sometimes the barometer of when to sacrifice quality and when to sacrifice scope is hard to read. You need to know how to best deal with both strategies instead of being told that you should avoid one entirely.

To benefit the most from reducing Quality…

Track it

Know when, where, and why shortcuts were taken, and track the speed of your team to ensure that these issues aren’t leading to a team-wide slowdown.

Tracking is an incredibly important aspect of quality reduction, because of two insidious aspects of technical debt

Technical debt builds one line at a time

Technical debt can be both incredibly easy and impossible to payback

Technical debt builds one line at a time.

That means it’s difficult to realize when you’ve accrued too much of it because every small change, taken in isolation, is often acceptable. It’s only by looking at the total amount that you realize the magnitude of debt you’ve taken on in the technology.

Technical debt can be both incredibly easy and impossible to pay back.

Once you’ve amassed a certain amount of technical debt, it becomes nearly impossible to pay back and maintain speed without exponential cost increases (often in the form of salaries, unhappy customers, and lost opportunities).

However, other times, you never have to pay back technical debt because of some change in the environment (eg. the feature is no longer needed).

Which one is which is difficult to determine at the time you accrue it and requires forethought and experience.

If you aren’t tracking the speed of delivery on your team in the form of an empirical metric, such as cycle time, deployment frequency, or lead time, you are driving blind and relying on luck. Don’t rely on luck to succeed — make your own luck.

Don’t take Quality shortcuts in your core

Set higher quality bars for things that are core parts of your technology or business, functionality that is used in many places, or parts of your system that you can’t afford to get wrong (eg. security, financials).

These are the parts that will experience the most change and iteration and form the foundation of the rest of your product. Other ideas you have will branch off of or integrate with these core pieces, and it’s important to get these areas right in order to keep as many options open as possible and to sustain speed.

This means if you’re a payments company, don’t skimp on testing or maintainability of your payments infrastructure. If you’re a workflow company, make sure you really think through your workflow architecture.

If you don’t, you might end up with a fragile tower of cards that you can’t easily add to, integrate with, or change.

Do take Quality shortcuts in your peripheral

Got a script that only needs to be run once? How about a minor feature that only 1% of your customer base is going to use? Up against an RFP deadline and need a tick-off-the-box feature?

In these cases, it’s OK to take quality shortcuts to get it out the door faster. The benefits of doing so can outweigh the long-term costs, and buy more time to fix it.

To benefit the most from reducing Scope…

Don’t cut to nothing

Minimum viable products often experience so many scope cuts in the drive to get them to market that teams accidentally turn them into minimal valueless products.

Because they lack any value, these projects fail to get traction with the users or customer base, and a potentially promising route gets cut short because it didn’t solve the core problem of the customers.

Avoid this trap — make sure you actually include the parts that do provide value. Don’t dismiss an idea outright just because it didn’t work the first time, especially if the execution was sloppy or incomplete or interrupted. Solve the core problem.

Ensure you prioritize iteration

One of the biggest issues I see with startups is a lack of focus. They bounce around from idea to idea, never really seeing the success they could have had they focused on any handful of them.

They deliver minimum viable products (if that) and then move on to the next big thing instead of building on their initial attempt with market feedback and iterating.

Because they fail to iterate on their MVPs, these startups quickly get overshadowed by competitors who do, losing what advantage they gained by getting to market quickly.

Competitor advantages deepen as time goes on because while the startup floats from product idea to product idea, the competitor focuses, iterates, hones, and refines their MVP into a leading, world-class solution.

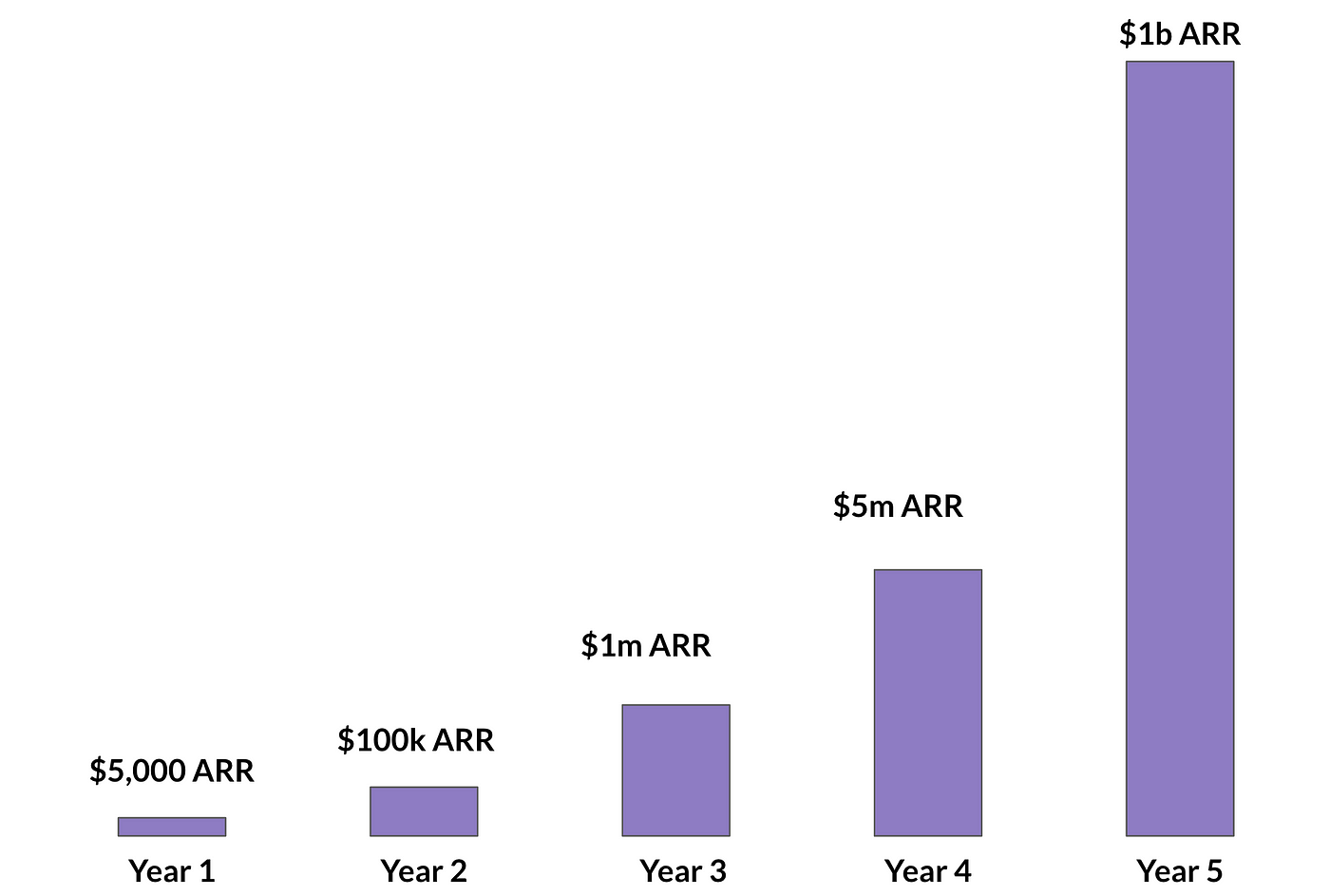

Part of this behavior is driven by inexperienced product leaders. If you’ve ever seen a startup investment pitch deck or an idea presentation from a junior product manager, you’ll know what I mean. They are filled with charts that indicate hockey-stick growth and completely unrealistic projections that somehow magically include some inflection point that explodes into exponential growth.

How can any iteration compete against that? How can an idea that leads to a 1% revenue improvement compete against a 10,000% revenue improvement? They can’t — iteration and small improvements will always lose the prioritization argument against the next big idea, every single time.

It’s a rigged comparison with lies for numbers. Everyone is almost invariably over-optimistic of the potential of their next big product idea.

This is why it’s important to ensure that you dedicate time and resources to iterating on what you’ve already built, regardless of whatever is on your roadmap. If you don’t, your product will just float from idea to idea without any purpose or direction, and you’ll lose the momentum you build.

Those scope shortcuts you took will quickly turn into dead ends and wasted effort without iteration.

Never scope out company-destroying aspects

There are just certain things you shouldn’t scope out — security in payments, legal requirements, and consumer safety are just a few for starters. By scoping them out, you might move faster but you play fast and lose with a company-destroying level of risk. You want to take risks judiciously, not take on risks like a gambler.

Use this as a guide — how would you feel if the fact you scoped it out of your product was on the front page of a newspaper tomorrow? Don’t care at all? Go ahead and scope it out. Slightly embarrassed? Think about it first. Shaking in your boots and looking for plane tickets out of the country? Don’t scope it out.

Build reusable libraries to avoid having to scope out aspects

An aspect only has to be scoped out if there is a cost associated with keeping it within the scope. However, if there is no cost associated with it, scoping it out is unnecessary as the shortcut would not decrease costs in any meaningful way.

Developers can achieve a near-zero cost scope addition by creating or using reusable libraries and frameworks that have been proven to work, and by establishing patterns so that problems solved in the past do not have to be solved again. These can be anything — audit libraries, feature flags, image uploading subsystems, or maybe payments APIs.

Creating and using reusable code enables engineers to easily and quickly include things that would have otherwise been scoped out, leading to a better overall product.

Startups deliver rapidly through the proper application of shortcuts. These shortcuts to both quality and scope determine the speed you move during the short-term and long-term. Balance these judiciously to ensure your startup has the technology it needs to succeed and thrive now and in the future.