How to Design Software — Plugin Systems

Learn how I made a chatbot extensible by designing and building a plugin system to make it modular.

Learn how to build a plugin system to allow others to extend your program’s functionality and modularity, using a chatbot as an example.

When I was younger, I had a top-of-the-line gaming computer. I spent thousands of hours playing games like Team Fortress 2, Minecraft, Guild Wars, and Age of Empires.

One of my favorite activities after I had thoroughly explored a game was the practice of modding. Modding allowed you to create or download packages of software that changed or added to how the software behaved — new levels, textures, or even game mechanics! The possibilities were limitless.

Now that I’m a software developer, I have a better understanding of how many of these programs supported such massive extensibility.

They used a concept called plugins.

Plugin systems

Plugins allow you to write subprograms that then hook into or are attached to a larger program. These subprograms then run, modifying or adding to the behavior of the running program.

In order to write a plugin, the program itself has to be written (or hacked) to support the plugin. Once this capability exists, you can “plug and play” tremendous amounts of functionality.

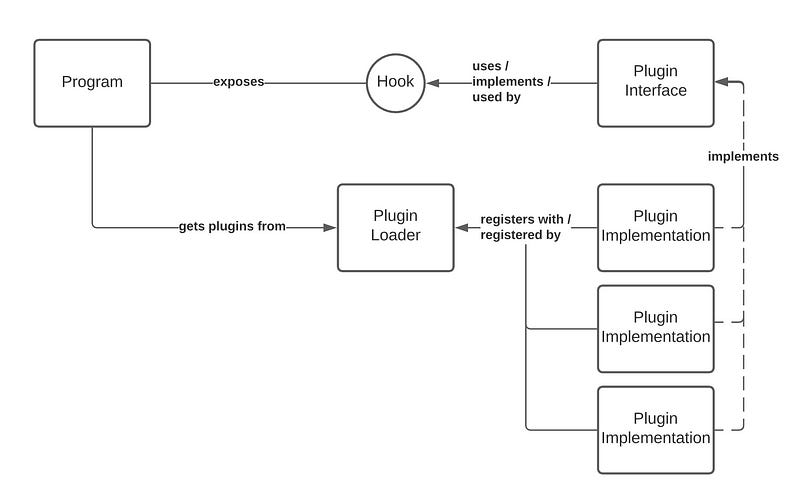

The Concepts

Plugin systems come in many shapes and forms — to illustrate the design, the following basic concepts can help frame your thinking:

The program

The first piece is the program itself, the thing whose behavior you are actually trying to enhance or modify. This might be a game like Skyrim or it might be a business application like Sketch. It might even be your own program!

Whatever it is, it offers some set of behaviors and capabilities that you want to change. More importantly, it does not know about the changes you want to make.

The hook

Something in the program you’re trying to change has to run the code it doesn’t know about. Otherwise, it would be very difficult to change the behavior.

This point at which the code is run is called the hook. Rails’ model callbacks or Vue’s component lifecycle hooks are examples of hooks used out in the wild.

A simple example of a hook is below:

See how the onSaveHook has no behavior. In this example, it is expected that this behavior will be filled in by a class extending RecordSaver and implementing new behavior in the subclass.

The plugins

The plugins are the code that other people write and “plug in” to enhance the capabilities of the program.

You could potentially extend the RecordSaver class from the example above with functionality such as below:

class LoggedRecordSaver < RecordSaver

def onSaveHook()

puts 'Saving record.'

end

endNow when LoggedRecordSaver#save() is called, it will print Saving record. after calling #writeToDisk() to the console. This behavioral enhancement was done by extending RecordSaver — a basic way to enhance a program’s behavior.

Note also that RecordSaver doesn’t know anything about LoggedRecordSaver: the coupling is unidirectional.

The loader

Having a plugin is useless if it never actually manages to run. Something needs to load the Plugin to start executing its code.

There are a lot of techniques available to actually make this happen — two methods are:

Plugin-driven, where the plugin knows how to access the program and self-registers.

Program-driven, where the program knows how to find plugins and loads any it finds.

In plugin-driven loading approaches, the program provides a method by which the plugin can register itself with the program. In program-driven loading approaches, the program finds a plugin, such as by loading all files in a folder with the name *_plugin or by loading a manifest.

A Chatbot Written Using Plugins

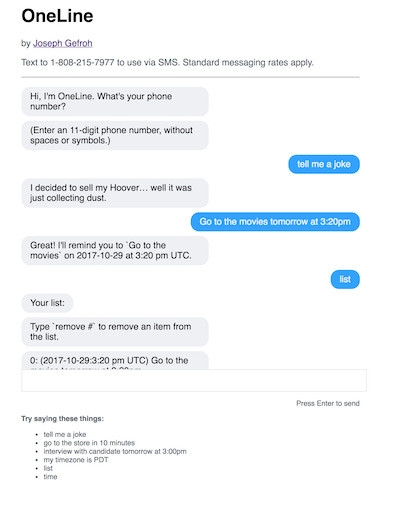

A while ago, I spent a weekend writing a chatbot, OneLine, to tell me puns and send me reminders using natural language.

The approach was simple: receive a message, do something arbitrary with it, and send back a response. To build all this, I build a basic plugin system that implemented the concepts mentioned here.

The loader

OneLine had a part of the program, a subset of static methods on the Core::Plugin module, define an implementation to:

Load a

plugin(#load)Track all loaded

plugins(@@plugins)Call all loaded

plugins(#call_all)

Note that the loader and the hook are both combined in this example.

The loader is the load function that Plugin implementations can call to make the program aware of it.

The hook is very explicitly a call_all function that is called when the program receives a message.

The plugin interface

It also defined an expectation for plugin implementations — behaviors all plugins should support. In this case:

A check to see whether the plugin should run or not (

#process?)A method that will be called to run the plugin (

#process)A standardized response the plugin was expected to return (

#to_response)

The #process function is called by the hook (upon receipt of the message).

The plugin implementations

Finally, there are the plugin implementations that parse and interpret the message and do something with it. I made plugins to:

Tell me a joke (

lib/oneline/jokes)Keep track of my to-do list (

lib/oneline/scheduler)…and more!

The simplest example, a plugin that tells you the current time, is below.

That’s It!

Pretty straightforward! Approaching things in this manner left room for extensibility by others, kept different parts of the code segmented and isolated, and allowed me to build and support extensions, such as supporting a web server or conversations via SMS.

While plugin systems aren’t appropriate for all scenarios, they can be highly useful in some cases.

Full Source Code Repository

Feel free to check out the full source code for the chatbot (specifically in the lib/oneline folder):

JGefroh/oneline

OneLine is a personal assistant chatbot intended to simplify my life. You’re a busy person with many important things…github.com

Did you like this article? Let me know in the comments, or connect with me on LinkedIn!