On development - How to design an effective intake process

Wrangle the chaos of startup life through the implementation of lightweight, efficient processes.

Wrangle the chaos of startup life through the implementation of lightweight, efficient processes.

Process is an afterthought for many tech startups and an intake process is often the last thing on leadership’s minds.

After all, they haven’t needed it so far. In the day-to-day chaos, things have happened and progress was made just fine without any formal process.

They may even have started thinking that an intake process isn’t even necessary and would just slow things down. Perhaps they’ve come to believe that their team has somehow found some special trick to make such process completely unnecessary.

They deceive themselves. It’s understandable how inexperienced engineering leads get lulled into this dangerously false sense of security. The lack of structure that was once the competitive edge of a small team of 10 quickly becomes the achilles heel for a larger company of 50 or 350.

Growth changes the game

As startups grow, the complexity of the projects grows and the inter-team collaboration demands increase exponentially.

Focuses shift. Tasks get re-prioritized. Projects get cancelled and renewed. Change is constant. Many requests inevitably slip between the cracks and get lost.

From the outside, the development team becomes a black hole — nobody in the organization quite knows what the developers are working on, and it’s already hard enough to understand just exactly what a developer does without this.

External teams without insight into the day-to-day of development begin to lose awareness of the status of requests they made — requests that they desperately need completed to move the needle on the company’s objectives. They waste time pinging individual engineers, or make false assumptions that cause their own initiatives to abruptly come to a screeching halt.

The means by which a request actually gets done ends up becoming opaque. Whether a request gets fulfilled or not gets done becomes determined by the whims of the person being asked, informed by the relationship between the asker and the askee. It becomes a barter economy where important things get dropped while less important things get done just because someone was friends with an engineer or they exchanged favors. This doesn’t make for an effective prioritization culture — it is a pathological, political one.

Cultures like this sow the seeds of doubt about the development team’s effectiveness and, over the long-term, turns into mistrust of the development organization as whole—a perception all engineering leaders should strive to change.

Effects of a good intake process

If intake processes become necessary after growth, how does it actually help?

It helps individual developers be more effective.

It allows for effective planning across the entire organization.

It provides signals that can be acted upon.

It helps ensure prioritization is explicit and obvious.

It helps individual developers be more effective.

At some point in their career, every software developer will have someone in another department asks them for a favor. The initial request is often small — perhaps it a “really quick” text change, or a small fix for a bug that’s been bothering them for a long time. The ask might be made in a passing comment in the hallway or via a short email:

The developer does it, because “Why not?” —it’s only going to take 10 minutes. The next day, they get another request, which they dutifully do. Then, another….and another…. and another. Soon, others are also making requests because they heard that’s how things get done. The developer doesn’t say no. They just start working late or slow down on their other tasks. Ah, the curse of being reliable.

This is the invisible hand of hidden work. It drags on teams causing immeasurable amounts of inefficiency and distraction. the hidden work is impossible to accurately plan for because it happens in the shadows of people’s individual inboxes and water-cooler conversations.

Having an effective intake process shines a spotlight on hidden work. It doesn’t mean that this hidden work never gets done or is never prioritized — it just means that everyone is aware of it, not just the people in the conversation.

High visibility lets you account for all of the hidden work in your planning, ensuring resourcing, prioritization, and scheduling are appropriate.

It allows for effective planning across the entire organization.

For external teams operating in an environment without an intake process, making a request may feel like “tossing something into a black hole”. When will it be done? Who knows. Will it get done? Roll a dice. Will you be told when anything happens on it? Probably not.

Operating in a zero-information environment like that can only lead to tragedy. For example, Sales may commit something with a key customer believing a request they submitted weeks ago had been completed, when in reality it may not even have been started! When they find out a week before it is due that it hasn’t even been looked at yet, it causes a fire in engineering to rush and get it out, or an unhappy key account.

Incidents like this build frustration in the organization and ultimately hurts cross-functional collaboration.

An effective intake process importantly makes status and progress visible to the requestor, providing clarity and improving cross-departmental collaboration and trust.

This clarity promotes better synchronization as dependable intake cycles can be planned with in mind, especially important when collaborating with departments that have longer cycles, such as Marketing and Sales for go-to-market initiatives.

It provides signals that can be acted upon.

Finally, an intake process helps maximize the long-term effectiveness of the development team by providing opportunities to collect trailing and leading indicators of how the team is doing.

It provides you an opportunity to get insight and take action based on the kinds of requests you are getting, or how long things are taking.

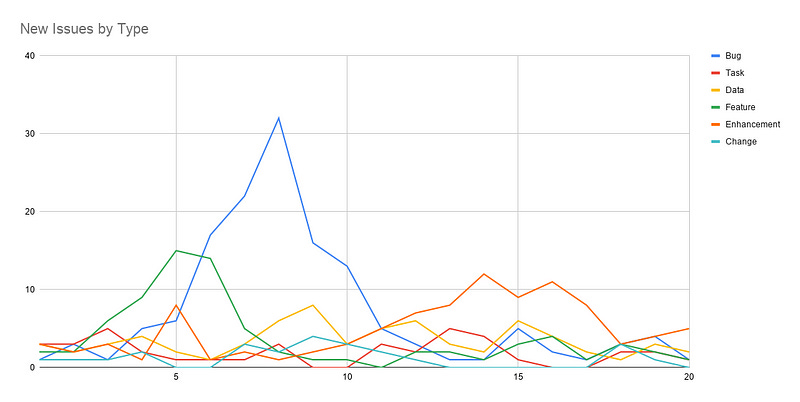

Suddenly getting an influx of bug requests? You may have a quality issue.

Getting an influx of data asks? Perhaps it’s time to expand the data science team.

Cycle time suddenly skyrocked? Perhaps requirements are not defined well-enough.

Whatever the case, you can’t get these signals unless you’re looking for them.

It helps ensure prioritization is explicit and obvious

Without an effective intake process, prioritization is often dictated by the person with the most acronyms in their title or the squeakiest wheel.

or smaller, less influential members of your startup, it’s hard to get prioritization and they may feel like nobody has their back. This is a problem that customer success and operations teams often have, despite being the front-line for user contact and the first-impression of your company many people get.

I’ve seen situations where companies were spending tens of thousands of dollars in salaries to solve something that could have been permanently resolved with just 10 minutes of developer time. Savings like this would never have been prioritized or even remembered to be addressed had they not been explicitly tracked.

How do you implement an intake process?

Implementing a new intake process is just about the same as implementing any process change in a company:

Define the desired effects

Define the inputs

Define the process

Define the outputs

Release and drive adoption

Monitor, improve, extract

Define the desired effects

Every process should have a purpose for existence. We must understand the impact we want our process to have on our environment, and then design the process to achieve that impact. If the effects aren’t needed, the process isn’t needed, and only a truthful examination of your context will determine that.

We addressed some of the desired effects above, but to restate them:

We want to help individual developers be more effective in the face of multiple streams of requests by giving them a process with which to manage those requests.

We want to improve planning across the entire organization by collecting, centralizing, and articulating all of the requests that would otherwise be hidden.

We want to make prioritization an explicit conversation by making it obvious what will get bumped if something else gets prioritized.

We want to identify long-term trends and act upon them by collecting, organizing, and analyzing the data we need during our day-to-day work.

Remember: always know what you’re trying to accomplish first before implementing a process. You don’t want to become a process-heavy bureaucracy — you want to be a nimble, but organized team.

Define the inputs

The inputs to the intake process are the intake requests themselves. In order to figure out the inputs, you’ll want to ask yourself two questions:

What kinds of requests will you intake?

What specific information does a request need to be fulfilled?

What kinds of requests will you intake?

In general, the following categories are a good place to start:

Bug — errors caused by defects in programming

Change — work needed due to a missing or incorrect requirements, or a change in environment

Enhancements — a small addition to existing functionality

Feature — new functionality

Task — a task that requires an engineer’s involvement (eg. running a script, setting up an environment, or grabbing data)

I personally found the additional following categories useful through my career:

Data — a request to fetch data for BI, analytics, operational use, etc.

Debt — a piece of technical debt

Maintenance — an activity that is required for continuing operations (eg. server updates)

Further categorization can be beneficial, but always balance it with the complexity costs. Keep it as simple as possible to promote adoption first, and then layer in evolutions.

What specific information does a request need to be fulfilled?

Once you know the kinds of issues you’ll intake, you’ll want to come up with a basic set of information you want to gather.

These might include:

Summary of the problem / request

Steps to reproduce a problem, if applicable

Identifiers that would be helpful (eg. email addresses, IDs)

Due date / Urgency

Importance / Priority

Scope of Impact

Stakeholders involved

Don’t ask for too much information

If a requestor has to provide 100 pieces of information just to file a request, they’re less likely to report it using the process you provide and instead fall back on the easier method of privately messaging an engineer.

You don’t want too heavy a gating mechanism for intake as the alternative will decrease engineering productivity and leads to untracked work which makes accurate planning more difficult and throws off forecasts.

The flip side of asking for less information is that yes, whoever triages may need to spend extra time hunting down information. I consider it a small price to pay, but your context will provide the clearest answer.

Create templates or forms

If possible, create pre-made templates or forms that people can just fill out. This will help guide the way they structure their intake requests to better match the format you desire.

Be sure, however, to leave it open-ended. If you create a form that is too strict or hard to use, people will take the easy way out.

Make sure it matches your team

Some teams are filled with developers who love to talk with stakeholders and understand problems. These teams benefit from open-ended problem statements that leave freedom for initiative and flexibility.

Other teams are filled with task-takers who just want to go heads down and get exactly what they need told to them. These teams need exact details that are well defined and researched.

Make sure you don’t give orders to your problem-solvers and make sure you don’t give ambiguous problems to your solution-implementers (unless you’re specifically trying to change the culture, but that’s a topic for another day).

Define the process

Once you define the inputs, you’ll want to define the intake process itself. The answers to these questions will depend on the context of your startup.

What are the stages a request will go through?

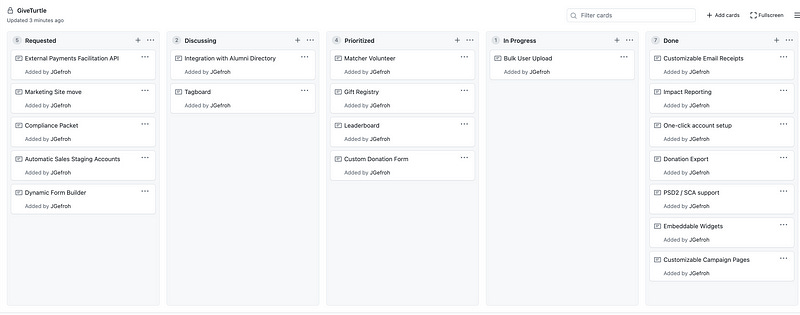

You’ll want a manageable pipeline that a request can go through, depending on your development lifecycle.

I recommend statuses that start simple — a sample “happy path” is below:

Requested — the request was requested by the requestor

Discussing — the request is being discussed by the development org

Prioritized — the request has been prioritized for development

In Progress — the request is actively being worked on

Done — the request has been fulfilled

I also recommend having some sad paths to handle the realities that not everything will be worked on:

Needs Information — the request does not have enough information to execute

Iceboxed — the request is not going to be worked on

Deprioritized — the request was previously prioritized or in progress, but is now being deprioritized

A key thing to remember when designing the stages: you don’t have to add every detail of the lifecycle of the request — only those that are relevant to the requestor.

For example, if you have a code review stage in your development process, you don’t need to add it as a stage to your intake process — it can still be considered “in progress”. That’s because the fact it is in code review is irrelevant to the requestor and from their perspective it just isn’t done yet.

The primary audience for intake is the requestor, not the development team.

How often will the intake be curated?

It’s important to ensure that you are managing and curating the intake queue at a speed that is relevant to your operating context. The speed with which you perform the “intake loop” is the intake’s operating tempo.

An intake process that responds to requests every 2 weeks is not likely to be effective in an environment where the situation changes daily. Likewise, an intake process that you curate daily is not an efficient use of your time if everyone interacts with it monthly. Use appropriate timelines for the situation.

I recommend starting with a daily cycle to curate the bugs, fires, and smaller requests. Add in a larger weekly cycle to curate and prioritize the product-related asks with the product team.

What you shouldn’t do is check back only once every 2 week sprint. The rate at which requests come in is likely going to overwhelm you and frustrate stakeholders. Stick to a tempo that’s at longest weekly.

What are the expectations?

Expectations should be clear and well defined for both requestors and the intake team.

In general, I recommend at least these things:

Establish a response-time SLA

Appoint a single responsible, empowered stakeholder

Keep communications on or near the ticket

Establish a response-time SLA

Establish response-time expectations with people who interact with the intake process. I recommend an SLA of 48-hours to start for any new intake item, and a 24-hour SLA for any back-and-forth Q&A needed to establish clarity.

An important thing to note: this is a response SLA, not a resolution SLA. The response can be “no movement” or “we’re still investigating” or “we’ll get back to you”. Sometimes the answer can be “we will discuss this in our next cycle”.

The important part is that everyone is aware of who has the responsibility to move the ball forward, and whether effort is being placed towards moving it forward or not.

Appoint a single responsible, empowered stakeholder

I also recommend, if possible, that all requestors must appoint a single stakeholder responsible for communicating in a timely manner with the intake manager, answering any questions necessary to complete the issue.

This individual must be empowered to make decisions and be the voice of authority for the stakeholder, and should be responsible for coordinating with their department. This helps wrangling differing opinions easier.

Keep communications on or near the ticket

One of the challenges of obtaining context for a ticket is the fact that the conversation happens in dozens of places — email threads, meetings, private messages, etc.

Try your best to get agreement to document the requirements and asks within the ticket itself, or a link from the ticket to whatever central document repository is being used. If a decision is made, it should be recorded before being considered finalized.

In an ideal world — all the context necessary should be obtainable by anyone who starts at the ticket.

What tool should I use?

There’s a plethora of project management tools out there. I recommend using one that:

Your entire organization can easily adopt or already uses

Supports adding custom data points, such as estimates or tags

Supports adding your own pipeline stages

Supports having multiple pipelines to allow for multi-team intake

Supports raw data extraction so you can slice and dice in excel

I’ve found the newer version (and the really old versions) of JIRA to be an excellent tool for organizations, even if it is a bit heavy on the administration side. Tools like Asana, Smartsheet, and Favro can work as well, although their simplicity makes it harder to extract insights and feel a but clunky at times.

Avoid using a tool that only your engineers can use, unless your intake is specifically for engineers. You want your intake publicly visible and accessible, and using a tool that 90% of your company can’t use defeats the purpose of the intake process, and will lead to a lot of administrative overhead caused by copying tickets back and forth from system to system.

What about the old stuff?

There’s a possibility that there’s already many items in your organization’s backlog — added on by months or years of chaos. I’ve seen backlogs tens of thousands of requests deep — a dream wishlist of things that will never be done.

I recommend throwing it out.

The knowledge captured in those tickets is likely outdated, not particularly fleshed out, or no longer relevant to your organization. It is knowledge debt that acts as cruft and defocuses from the actual important items. It would take significant time to go and sort through it all — time you don’t have. Throw it out.

Yes, it is painful. Don’t worry — the important stuff will come back on its own.

If you must, keep some as examples

You’re probably already aware of some items you need to do. For the stuff you don’t throw out, you can rewrite in an ideal way and put these into the intake as examples of what you want the intake items to look like.

There’s many more questions you’ll want to answer

These aren’t the only questions, but they form a great conversation starter as you think about the process design:

How will people submit requests to the intake?

How will a new request be prioritized?

What happens if a request is picked up to be worked on?

What happens if a request is de-prioritized?

What happens if a request is broken up?

What happens if a request is a bigger piece of work than expected?

What happens when a request is released and done?

What are the expectations on the development team once a new request comes in?

Who’s going to be responsible for sorting through and responding to new intake requests?

Once an intake request comes in, who’s going to ensure it gets prioritized or discussed?

Releasing a new intake process

So, you understand your goal, you’ve defined the inputs, and you’ve designed the process. Now you’re ready to have people start using it and contributing to it.

The good news is that it’s as easy as having people start asking you for stuff, which most people are quite willing to do.

The bad news is that not everyone will want to follow a process to do the asking, and you’ll have to do things to remove any friction against following it.

Put it in one place

Good intakes are centralized. A requestor shouldn’t have to hop onto 10 different tools or chase down a bunch of random links. Every single person should be able to see everything that everyone has requested in one, single location. Make it as obvious as possible.

I’ve had a lot of success making subdomains or forms specifically for internal intake such asintake.companyname.com.

Communicate it

As I’ve written about in the past, repetition is the key to effective communication. When you release your intake process, communicate it until you’re tired of hearing yourself, and then communicate it some more.

At minimum, people should know:

the fact there is a new intake process

how to use the intake process

where to find the intake process

what the benefits of using the intake process are

what the costs of not using the intake process are

Send a link to every single team in the company and make sure they know where to find it. Send emails. Send instant messages. Mention it in conversations. Do an announcement at the next all-hands.

Redirect everyone to it

Even after you release your intake process, people will still not use it — either due to forgetfulness, lack of time, or lack of desire.

Be patient, and redirect everyone to use the intake process. Every time you see an email come in asking to take engineering time to do something — ask them to make an intake ticket. If you see a Slack message that’ll require development effort, ask them to file an intake ticket with the necessary details.

Instruct others to redirect them, too

The weakest link in the intake process are the people who say yes when asked out-of-band. Oftentimes when releasing a new intake process, some engineers on the team do not necessarily want to be the ones who have to say no. Perhaps they truly do think they have enough time to do small requests.

By this point you should have already sold the benefits of an intake process to the engineering team. Remind the engineers that they should present a unified front and redirect all requests to intake.

Note: that doesn’t mean they can’t work on it or they shouldn’t ever do anything someone else asks. It just means that it has to be recorded. As an aside, engineers benefit because now they have an excuse for saying no that allows them to save face — “my manager says we have to follow the intake process”.

Stay on top of it

You should either fully expect to be doing all of the intake curation and administration yourself for the first month or two, or find an ally who is really gung-ho about it. I’ve had success with both, but your mileage may vary.

Over time, as the intake process gets adopted, you can start shifting the curation burden to the developers (which is a minimal left to their day-to-day) and the team leads.

In the mean time — check the intake queue several times a day. Be responsive. Follow up with people.

Don’t drop the ball

The beginnings of an intake process are incredibly fragile. You need to have people trust it and accept the increased friction in making a request with the benefit of having increased visibility and a better response rate. Sometimes going the extra mile to ensure a request is fulfilled for an underserved stakeholder group makes sense, even if it isn’t a priority one.

Don’t use it as an excuse to not do something important

Sometimes truly important things will come outside of the process. Do your best to put it into the process (such as writing a ticket after the fact and pointing people to it), but don’t let the process prevent you from doing the important things. Remember: your organization is not here to work for the process, the process is here to work for your organization.

Dealing with the non-adopters

Some people just won’t use your intake process when you release it. They may still continue passing along email threads, direct messaging people, etc. Guilty parties are often the three-letter acronyms (CEOs, CFOs, CMOs, etc.) or frequent requestors who have already seen success in accomplishing their goals without using the process.

There’s a few strategies you can use — both carrot and stick.

Carrots

Make the issues for them whenever they make a request, and point them to the link to that specific request. Tell them you’ll add any status updates to that ticket and that they should provide any information on the ticket itself so it doesn’t get lost.

If they start using the intake process, I would try to accelerate / prioritize their ask, even if it is technically “low priority” as a reward for them following the process. As it becomes routine over time, you should have to use fewer and fewer carrots.

Sticks

Tell them that you can’t do anything they write a ticket and they commit to a single stakeholder, a response SLA, or whatever it is you need. Then, don’t do anything that doesn’t meet those requirements.

This is the brute-force method, and can likely cause a lot of squabbling. However, it is a highly effective forcing function. If you have the political clout to weather a managerial escalation or two, it’s a very rapid way to start some great conversations surrounding the importance of the intake process (a small tip for managing up and out).

The important caveat here: have a short-term memory. Even if they don’t follow the intake process 50 times, as soon as they do at least once, reward them for it! Don’t let grudges get in the way of organizational effectiveness. The tit-for-tat strategy in game theory provides a good model for this.

A final option

If you do have a couple stragglers who simply adamantly refuse to adopt the intake process, you have two choices:

Don’t do what they ask, ever.

Make the tickets yourself.

If you do end up having to make their tickets yourself — don’t despair! You still get the benefits of tracking and conscious prioritization for the effort.As an added bonus, you can say that you’re project managing the stragglers’ projects and get a sweet bonus.

Monitor, Improve, Extract

After a while, you should have an intake process that is being curated and used by most of the company. Now, you’re ready to start improving things and extracting the long-term benefits.

At minimum, you should have enough information to know:

How big is the queue?

How fast are items coming in?

How fast are items being responded to or resolved?

What kinds of requests are we receiving / completing?

Are certain stakeholder groups over-represented in requests?

Operational Efficiencies

If you follow lean principles or queue management theories at all, you can apply them highly effectively to the intake process to min-max effectiveness and manage towards things like improved cycle time or smaller queue sizes.

If you use a tool that can track when items move from phase to phase, you can do rapid analysis to identify key metrics like Cycle Time and Lead Time. Pairing that data with data on dates of deployments and releases can enrich the insights you get by helping you identify specific projects that may have caused issues.

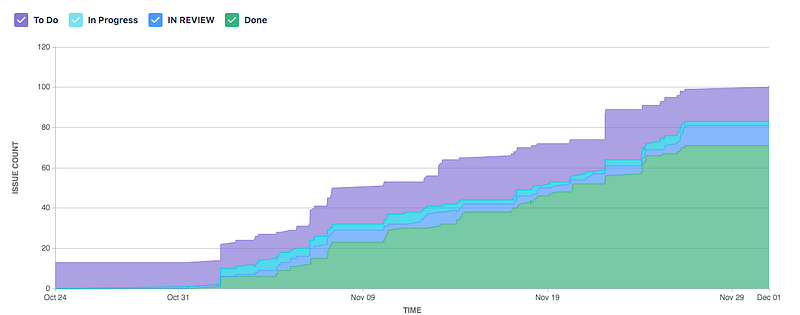

CFDs

Cumulative Flow Diagrams can tell you whether bottlenecks are forming, the rate of change of the inflow and outflow, and more. They are a great way to help manage team work execution.

Category Trends

Categorization of the types of requests you are getting can provide actionable insights into your development effectiveness and acts as a good trailing indicator that can inform hiring or development strategies.

There’s a surprisingly large amount of thinking that goes into something as small as setting up an intake process. The hidden complexities can have second and third order effects that can make or break team effectiveness.

It’s thinking worth doing.

Getting an intake process juuuuuust right for your organization is a journey— use this post as a starting point to help guide the conversations to be had, not as a concrete dogma.